Anticoagulation Dosing Calculator

Recommended Therapy

When someone has both kidney disease and liver disease, taking a blood thinner becomes one of the most dangerous balancing acts in medicine. It’s not just about avoiding clots-it’s about not bleeding out. The drugs we use to thin blood, like warfarin and the newer DOACs, don’t work the same way in people with failing organs. And the data? It’s messy, incomplete, and often contradictory. What works for a healthy 70-year-old with atrial fibrillation might kill someone with end-stage kidney failure or advanced cirrhosis.

Why Kidney and Liver Disease Change Everything

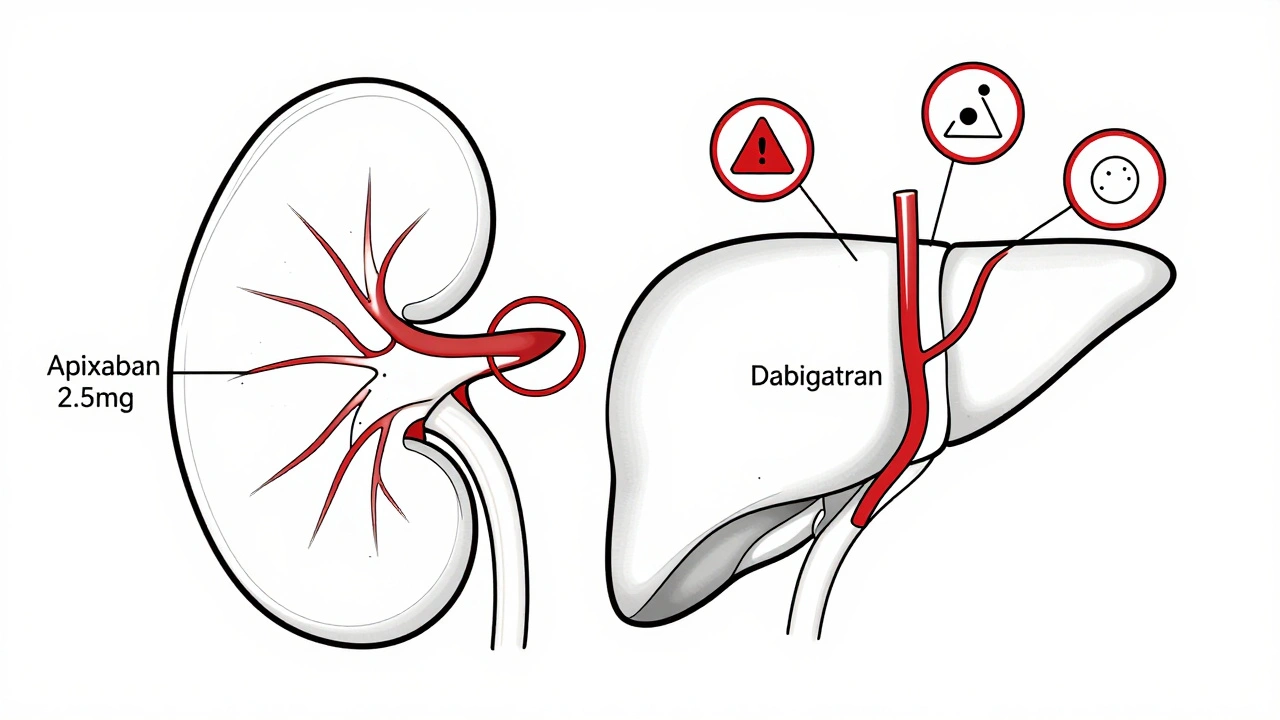

Most blood thinners are cleared by the kidneys or liver-or both. In a healthy person, that’s fine. But when the kidneys are failing, drugs like dabigatran build up fast because 80% of it leaves the body through urine. Rivaroxaban? About a third is cleared by the kidneys. Apixaban? Only 27%. That’s why apixaban is often the only DOAC even considered in advanced kidney disease. But even then, you can’t just give the normal dose. The body can’t handle it. Liver disease is even trickier. The liver doesn’t just clear drugs-it makes the proteins that help blood clot. In cirrhosis, the liver can’t produce enough clotting factors like II, VII, IX, and X. But it also stops making natural anticoagulants like protein C and S. So the body is stuck in a weird middle ground: not quite clotting, not quite bleeding-but dangerously close to both. Add in low platelets from an enlarged spleen (which happens in 76% of cirrhosis patients), and you’ve got a ticking time bomb.How Kidney Function Changes Your Options

Doctors measure kidney function with eGFR-the estimated glomerular filtration rate. If your eGFR is above 45, most DOACs are safe at standard doses. But once it drops below 30, things get serious. For eGFR between 30 and 44, you have to cut the dose of some drugs: apixaban from 5 mg to 2.5 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban from 20 mg to 15 mg once daily, edoxaban from 60 mg to 30 mg. Dabigatran? Just avoid it entirely. It’s too risky. In stage 4 or 5 kidney disease (eGFR under 30), the European Medicines Agency says no to rivaroxaban and apixaban. But the FDA says apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is okay, based on a post-hoc analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial. That study showed apixaban cut major bleeding by 70% compared to warfarin in patients with eGFR under 30. That’s huge. But here’s the catch: those patients weren’t on dialysis. And dialysis changes everything. For patients on hemodialysis, studies show apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily gets you a blood level of about 47 ng/mL-less than half of what you’d see in someone with normal kidneys. Rivaroxaban 10 mg daily gives you 78 ng/mL. Warfarin? It’s still used here, but you need to check INR every two weeks instead of monthly. And even then, it’s unpredictable. One study found only 45% of dialysis patients on warfarin stayed in the therapeutic range for more than 60% of the time. That’s worse than flipping a coin.Liver Disease: The INR Lie

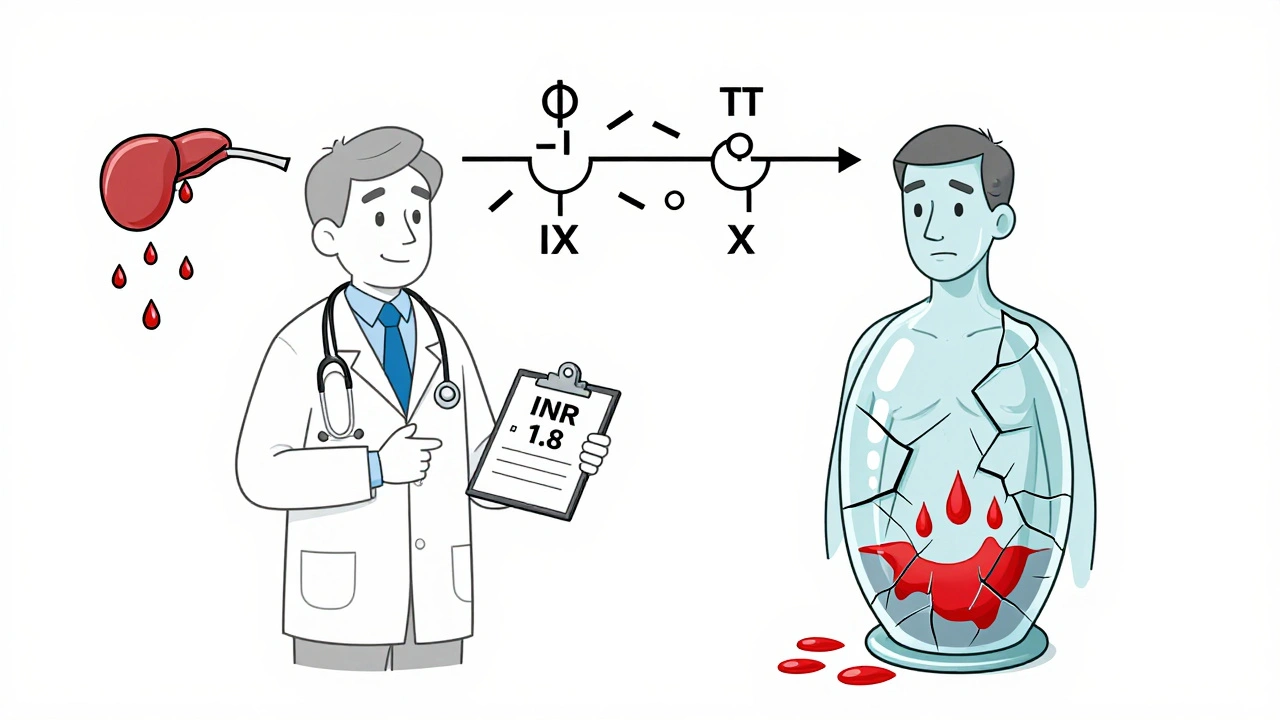

The INR is the go-to test for warfarin users. But in liver disease, it’s useless. The INR only measures vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. It doesn’t tell you about low platelets, low fibrinogen, or poor clot strength. A cirrhotic patient might have an INR of 1.8 and still be at high risk for bleeding because their whole clotting system is broken. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) says DOACs can be used in Child-Pugh class A (mild cirrhosis) at normal doses. For class B (moderate), use caution and consider lower doses. For class C (severe)? Don’t use DOACs. The RE-CIRRHOSIS study found a 5.2-fold higher risk of major bleeding in these patients. Some doctors still use warfarin here because we know how to reverse it with vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma. But the problem? It’s hard to keep the INR stable. One study showed the INR varied by 42% in cirrhotic patients versus 28% in healthy people. That’s chaos. And even if you get the INR right, you’re still missing the bigger picture: platelet function, fibrinogen levels, clot elasticity. Newer tools like thromboelastography (TEG) or ROTEM can give a full picture of clotting-but only 38% of U.S. community hospitals have them. Most of us are still flying blind.

Apixaban vs. Warfarin: The Data

When you look at real-world outcomes, apixaban comes out ahead in kidney disease. In the ARISTOTLE subgroup of patients with eGFR between 25 and 30, apixaban cut major bleeding by 31% compared to warfarin. It also cut intracranial hemorrhage by 62%. But in end-stage kidney disease, the story flips. For patients with mechanical heart valves, warfarin is still the standard. DOACs aren’t approved here, and no one wants to risk a valve clot because a DOAC didn’t work right. In dialysis patients, the 2021 Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation registry tracked over 12,800 people with atrial fibrillation. Only 28% got anticoagulation-despite 76% having a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or higher, meaning they were high risk for stroke. Of those treated, 63% got warfarin, 37% got a DOAC. Bleeding was lower with DOACs (14.2 vs. 18.7 events per 100 patient-years), but strokes were almost identical. That’s the trade-off: slightly less bleeding, same stroke risk.What the Experts Disagree On

There’s no consensus. The European Heart Rhythm Association says DOACs should never be used in dialysis patients. The American College of Chest Physicians says apixaban 5 mg daily might be okay. One nephrologist on Reddit reported 15 dialysis patients on apixaban 2.5 mg daily with zero bleeds over two years. Another described a patient who bled to death from a retroperitoneal hemorrhage on the same dose. In liver disease, some doctors say, “Treat the patient, not the INR.” Others say, “If you can’t measure it reliably, don’t treat it.” One hepatologist told me: “I’ve seen three major bleeds in the last year from anticoagulated cirrhotic patients. All of them were on DOACs. We didn’t check their platelets.” The truth? We’re guessing. We’re using pharmacokinetic data to predict clinical outcomes. But drugs behaving differently in the body doesn’t always mean they’re safer or more effective.Practical Steps for Clinicians

If you’re managing someone with both kidney and liver disease, here’s what you need to do:- Calculate eGFR with CKD-EPI-but know it’s inaccurate below 30 mL/min. Don’t trust it blindly.

- Use Child-Pugh score for liver disease. If it’s C, avoid DOACs. Period.

- Check platelet count monthly. If it drops below 50,000/μL, stop anticoagulation.

- For dialysis patients, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is the least bad option. Avoid dabigatran and edoxaban.

- Monitor INR every two weeks if on warfarin. If it’s swinging wildly, reconsider.

- Don’t assume a normal INR means safe. A cirrhotic patient with INR 1.5 can still bleed out.

- Consult nephrology and hepatology together. This isn’t a one-specialist problem.

What’s Coming Next

Two big studies are underway. The MYD88 trial is randomizing 500 dialysis patients to apixaban vs. warfarin, with results expected in 2025. The LIVER-DOAC registry is tracking 1,200 cirrhotic patients on DOACs worldwide. These might finally give us real answers. The FDA is considering new labeling for apixaban in end-stage kidney disease. KDIGO is updating its guidelines in late 2024, incorporating 17 new observational studies. That’s progress. But here’s the hard truth: we’re still treating patients with data from people who aren’t like them. We’re extrapolating from trials that excluded the very people who need these drugs the most.The Bottom Line

There’s no perfect answer. But there are safer choices. For kidney disease, apixaban is the most forgiving DOAC. For liver disease, if you must anticoagulate, start with apixaban at the lowest dose and monitor closely. Avoid DOACs in Child-Pugh C. Use warfarin only if you’re prepared for the chaos of INR management. The biggest mistake? Doing nothing because you’re afraid. Many patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced kidney or liver disease aren’t getting anticoagulation-even though their stroke risk is high. The risk of stroke isn’t zero. The risk of bleeding isn’t zero. But the risk of doing nothing? That’s often the highest of all.What You Can Do Today

If you or someone you care for has kidney or liver disease and needs a blood thinner:- Ask your doctor: What’s my eGFR? What’s my Child-Pugh score?

- Ask: Why this drug and not another?

- Ask: How often will we check my blood counts and kidney/liver function?

- Ask: What do we do if I start bleeding?

- Don’t assume a normal INR means you’re safe.

- Don’t skip your labs.

Can you take apixaban with end-stage kidney disease?

Yes, but only at a reduced dose: 2.5 mg twice daily. This is the only DOAC with FDA approval for use in advanced kidney disease (eGFR under 30 mL/min), based on data from the ARISTOTLE trial showing lower bleeding risk compared to warfarin. However, it’s not approved for patients on hemodialysis, and its use there is off-label. Studies show apixaban levels are lower in dialysis patients, but it still appears to be safer than warfarin in terms of bleeding. Always confirm dosing with a nephrologist.

Is warfarin safer than DOACs in liver disease?

Not necessarily. While warfarin has known reversal agents like vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma, its INR is unreliable in cirrhosis because the liver can’t make clotting factors properly. A patient can have a normal INR but still be at high risk for bleeding due to low platelets or poor clot strength. DOACs are contraindicated in Child-Pugh C, but in Child-Pugh A, they may be safer than warfarin because they don’t rely on liver metabolism as heavily. The key is not the drug-it’s the patient’s overall clotting status. Tools like TEG or ROTEM are better than INR, but they’re rarely available.

Why is dabigatran not recommended in kidney disease?

Dabigatran is cleared almost entirely by the kidneys-about 80%. In patients with eGFR under 30 mL/min, it builds up to dangerous levels, increasing bleeding risk without added benefit. Unlike apixaban or rivaroxaban, it has no dose adjustment that makes it safe in advanced kidney disease. The FDA and EMA both contraindicate dabigatran in patients with eGFR below 30. Even in moderate kidney disease (eGFR 30-50), caution is needed.

Can you use DOACs if you have both kidney and liver disease?

It’s possible, but extremely high-risk. Most DOAC trials excluded patients with both conditions. If you must use one, apixaban at the lowest dose (2.5 mg twice daily) is the least risky option. But you need close monitoring: monthly kidney and liver tests, platelet counts, and MELD scores. If platelets drop below 50,000/μL or MELD rises above 20, stop anticoagulation. Never assume safety just because a drug is labeled for one condition-it may not be safe for both.

What if I can’t afford reversal agents for DOACs?

This is a real problem. Andexanet alfa (for apixaban and rivaroxaban) costs $19,000 per dose and isn’t available in most hospitals. Idarucizumab (for dabigatran) is cheaper at $3,500, but it doesn’t work on other DOACs. If you’re on a DOAC and live in a community hospital without reversal agents, warfarin might be a safer choice-even with its INR issues-because you can reverse it with vitamin K and plasma, which are widely available. Talk to your doctor about access to reversal agents before starting a DOAC.

Comments

Aman deep

man i've seen this so many times in my uncle's case - end stage kidney disease, on dialysis, doc wanted to put him on apixaban but the family was terrified. we ended up going with warfarin just because we could get vitamin K at the corner pharmacy. still, his INR was all over the place. guess that's the price of living in a system where the best option is the one that doesn't need a $20k antidote. 🤷♂️

john damon

this is wild 😱 i had no idea DOACs were this tricky in liver disease. my aunt got put on rivaroxaban last year and her INR was 'normal' but she bled out from a sneeze. like... what even IS normal anymore?? 🤯

Monica Evan

the INR is a lie in cirrhosis and everyone keeps pretending it's not. i've been in ICU watching patients with INR 1.2 bleed out because no one checked their platelets or fibrinogen. TEG isn't magic but it's the only thing that tells you the real story. if your hospital doesn't have it, you're flying blind and pretending you're not. 🩸

Taylor Dressler

Apixaban 2.5 mg BID in advanced CKD is the least worst option, and the data supports it. The ARISTOTLE subgroup analysis is solid, and real-world evidence from nephrology clinics confirms lower bleeding rates compared to warfarin. The key is avoiding dabigatran and edoxaban entirely. Also, don't forget to check MELD scores in liver disease - a rising score means you're losing clotting capacity faster than you think.

Aidan Stacey

I’ve seen this play out three times in my ER and each time it was a nightmare. One guy on apixaban bled into his abdomen and died before we could get him to OR. Another? Stroke on warfarin because his INR was 'stable' at 2.1 but his liver was shutting down. We’re not treating patients here. We’re playing Russian roulette with pharmacokinetics and praying the gods of renal clearance are kind. This isn’t medicine. It’s a damn guessing game.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

so we're just gonna pretend that a drug designed for healthy 70-year-olds with atrial fibrillation is safe for someone whose liver can't make proteins and whose kidneys are basically a broken drain? brilliant. next we'll give insulin to a diabetic with a severed pancreas and call it 'evidence-based'. the system is broken and we're just rearranging deck chairs on the titanic while patients bleed out in the dark.

Jim Irish

The data on apixaban in advanced kidney disease is compelling. Dabigatran should be avoided. Warfarin remains an option if reversal agents are accessible. Monitoring platelets and MELD score is essential. Consultation with nephrology and hepatology is not optional.

Mia Kingsley

ok but have you seen the new FDA label? apixaban is basically being pushed on dialysis patients like it's a miracle drug. meanwhile, the real study that showed 30% higher stroke risk in dialysis patients on DOACs? buried in a supplement. i'm not saying warfarin is safe, but we're being sold a fantasy. also, why do we trust a trial that excluded 90% of the population it's meant for? 🙄

Katherine Liu-Bevan

The key point everyone misses: DOACs aren't safer in end-stage kidney disease because they're better. They're safer because they don't require constant INR monitoring. But in cirrhosis, that advantage vanishes. The real issue is the lack of tools to assess global hemostasis. Without TEG or ROTEM, you're treating a shadow. And yes, apixaban 2.5 mg BID is the least bad option for mixed disease, but only if you're monitoring platelets, MELD, and renal function weekly. Otherwise, you're gambling.

Courtney Blake

This is why America's healthcare is a disaster. We have a $19,000 antidote for a drug that shouldn't even be prescribed to people with failing organs. Meanwhile, in Canada, they just use warfarin and monitor it properly. We're overmedicating, under-researching, and charging people for the privilege of being a guinea pig. Apixaban in dialysis? That's not innovation. That's corporate greed dressed up as science.