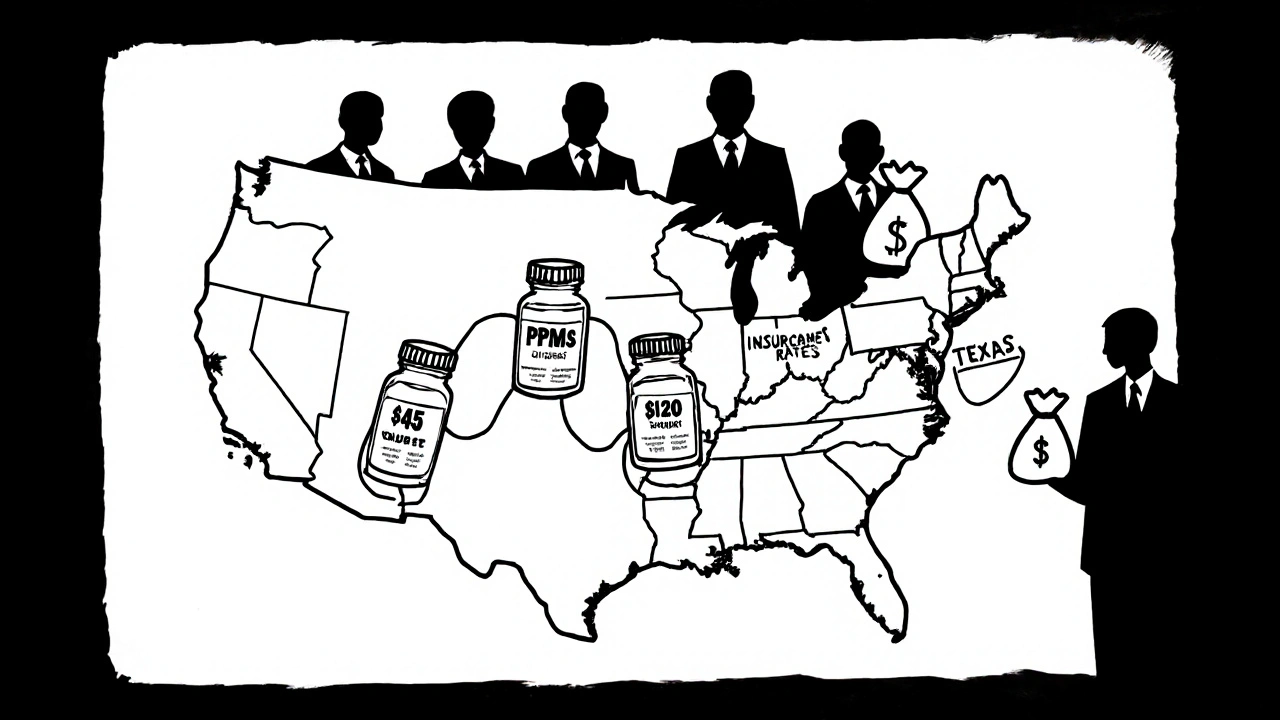

Ever bought a generic pill and been shocked by the price-only to find your neighbor paid half as much for the same thing? It’s not a mistake. Generic drug prices in the U.S. aren’t set by a national rulebook. They’re shaped by where you live, what insurance you have, and who’s behind the scenes pulling strings. In California, a 90-day supply of generic atorvastatin might cost $45 with insurance. In Texas, it could hit $120. Same drug. Same manufacturer. Different state. Why?

It’s Not the Drug-It’s the Middlemen

Generic drugs aren’t expensive because they’re hard to make. They’re cheap to produce. The FDA approved over 800 generic drugs in 2017 alone. But the price you pay at the pharmacy isn’t tied to production cost. It’s tied to a tangled web of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), insurance contracts, and state-level rules. PBMs act as middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drug makers. They negotiate discounts, set reimbursement rates, and decide which drugs get covered. But here’s the catch: PBMs don’t always pass savings to you. In many cases, they keep the difference. A 2022 study from the USC Schaeffer Center found U.S. consumers overpay for generics by 13% to 20% because of opaque PBM pricing. And those markups vary wildly by state. In states with weak transparency laws, PBMs can hide how much they’re really charging. In states like California and Vermont, laws force PBMs to report pricing data. That’s why patients in those states pay 8-12% less on average for the same generic meds.Medicaid Reimbursement Rules Are Different Everywhere

Medicaid pays for a huge chunk of generic drugs-especially in low-income communities. But each state sets its own reimbursement rate. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which updates monthly based on what pharmacies actually pay. Others use outdated benchmarks or private data from wholesalers. That means two identical pharmacies in neighboring states might get paid completely different amounts for the same pill. One gets reimbursed $2.50. The other gets $1.80. To stay in business, the second pharmacy has to charge you more out-of-pocket. You’re not paying for the drug-you’re paying for the state’s reimbursement policy.Competition Matters-Especially in Rural Areas

In big cities, you’ve got CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Target, and local pharmacies all fighting for your business. That competition pushes prices down. In rural areas? Sometimes there’s only one pharmacy. No competition. No pressure to lower prices. GoodRx data from 2022 showed price differences of up to 300% for the same generic drug between nearby states. In places like rural West Virginia or eastern Montana, you might pay $60 for a 30-day supply of metformin. In urban Oregon, the same script costs $18. It’s not about the drug. It’s about how many pharmacies are nearby-and how hard they have to work to get your business.

Cash Beats Insurance-But Only Sometimes

Here’s a counterintuitive truth: paying cash for generics often costs less than using insurance. Why? Because insurance companies and PBMs use complex formulas that don’t reflect real-world prices. Your copay might be $15, but the pharmacy gets paid only $5. The rest? Hidden fees, administrative charges, or profit for the PBM. In 2020, 4% of all U.S. prescriptions were paid in cash. Almost all of them were for generics. And 97% of those cash payments were cheaper than using insurance. That’s why services like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company and Blueberry Pharmacy are growing. They cut out the middlemen entirely and sell generics at cost plus a small markup. But here’s the catch: cash pricing only works if you know the real price. In states without transparency laws, you have no idea what the pharmacy paid. That’s where tools like GoodRx come in. They show you the lowest cash price nearby. But if you’re in a state with few pharmacies or weak price reporting, even GoodRx can’t help.State Laws Tried to Fix This-Then Got Blocked

In 2017, Maryland passed a law to stop generic drug price gouging. It said pharmacies couldn’t charge more than a certain percentage above the wholesale price. The goal? Protect consumers from sudden, massive price hikes. The federal courts shut it down. They ruled it interfered with interstate commerce. That’s the same legal argument used to block similar laws in other states. So while states can demand transparency, they can’t directly cap prices. Nevada tried targeting diabetes drug prices. The lawsuit was dropped-not because it was weak, but because drug makers threatened to sue under the Defend Trade Secrets Act. That’s how powerful the system is. States can shine a light, but they can’t turn it off.

The Inflation Reduction Act Helped-But Only for Some

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act capped insulin at $35 a month for Medicare users and set a $2,000 annual out-of-pocket limit for prescription drugs starting in 2025. That’s huge-for the 32% of Americans on Medicare. But what about the rest? If you’re under 65, have private insurance, or are uninsured? The law doesn’t touch your prices. Your state still controls your pharmacy’s reimbursement rules, your PBM’s pricing, and your access to competition. That’s why someone in Minnesota might pay $10 for metformin while someone in Georgia pays $45-both on the same insurance plan.What You Can Do Right Now

You can’t change your state’s laws. But you can change how you pay.- Always check GoodRx or SingleCare before filling a prescription-even if you have insurance.

- Ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?” Often, it’s lower than your copay.

- If you’re on Medicare, make sure you’re enrolled in a plan with the best generic coverage.

- For chronic meds, consider mail-order pharmacies or direct-purchase services like Cost Plus Drug Company.

- Call your state’s health department. Ask if they have a drug price transparency website. If not, push for one.

Comments

Alyssa Fisher

It’s wild how the system is engineered to confuse people. You’d think a generic drug is just a chemical formula, but no-it’s a labyrinth of PBMs, state reimbursement quirks, and pharmacy monopolies. The real tragedy? The people who need these meds most are the ones least equipped to navigate it. I’ve seen grandparents paying $80 for metformin because they don’t know about GoodRx. And no one’s teaching them how to fight back.

Transparency isn’t a luxury-it’s a basic human right when your life depends on it. Why should your price depend on your zip code? It’s like paying different rates for water depending on which side of the river you live on.

And don’t get me started on how Medicaid reimbursement rates are basically arbitrary. Some states use NADAC, others use data from 2012. That’s not policy-that’s negligence dressed up as bureaucracy.

Beth Banham

I just checked my last prescription. Cash price was $12. Insurance copay was $18. I’ve been paying more for years because I assumed insurance = cheaper. Never even asked. Feels stupid now.

Thanks for the reminder to always ask. Small things matter.

Brierly Davis

YES. This is the kind of info everyone needs. Seriously, go to your pharmacy right now and ask for the cash price. I did last week for my blood pressure med-saved $23. No joke. You’re not being rude-you’re being smart.

Also, if you’re on Medicare, check out your plan’s formulary every year. They change stuff and you don’t even know it. Little steps, big savings.

And GoodRx? Best app you’ll ever install. Don’t overthink it. Just use it.

Jim Oliver

Wow. Just wow. You actually think this is a problem? Let me guess-you also think people should get free healthcare, right? The market works. If you can’t afford $45 for atorvastatin, maybe you shouldn’t be taking it.

Also, GoodRx? That’s just a middleman for middlemen. You’re still paying for the system-you’re just being manipulated by a different one.

And don’t get me started on ‘transparency.’ That’s just a buzzword for ‘I want the government to fix my bad life choices.’

William Priest

Bro. PBMs are literally the reason your insulin costs $300. They’re not ‘middlemen’-they’re corporate vampires. They don’t add value, they just siphon. And the FDA approves generics like they’re approving crayons.

And you think state laws matter? HA. The courts shut down Maryland’s law because ‘interstate commerce.’ Like the Constitution was written by Big Pharma lobbyists. Which it kinda was.

Also, ‘cash beats insurance’? Duh. Insurance is a scam. You’re paying premiums so someone else can profit off your sickness. Wake up.

Cost Plus Drug Co is the only real solution. Everyone else is just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Ryan Masuga

Hey, I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been trying to explain this to my mom for months and she thought I was making it up. She’s on a fixed income and was paying $90 for her cholesterol med. I showed her GoodRx-she’s now paying $18. She cried. Not from sadness-from relief.

You’re right-we can’t change the system overnight. But we can change how we use it. That’s power. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Also, if you’re reading this and you’re young? Start asking about prices now. Don’t wait until you’re 65 and broke. This stuff matters.

Amber O'Sullivan

The whole thing is rigged and everyone knows it but no one does anything. States can't cap prices because of corporate lawsuits. PBMs hide their margins. Pharmacies don't tell you the cash price. It's all designed to keep you confused and paying more. And you think you're getting a deal with insurance? You're not. You're just paying someone else to take your money. Simple as that

Jennifer Bedrosian

OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN OVERPAYING FOR MY ANTIBIOTICS FOR 3 YEARS 😭 I WENT TO CVS AND ASKED FOR THE CASH PRICE AND IT WAS HALF WHAT MY INSURANCE CHARGED. I FEEL SO STUPID. I THOUGHT I WAS BEING SMART BY USING INSURANCE. NOPE. I WAS BEING SCAMMED. THANK YOU FOR THIS POST. I’M TELLING EVERYONE. I’M GOING TO POST THIS ON MY FACEBOOK. I’M SO MAD RIGHT NOW BUT ALSO SO GRATEFUL. I JUST SAVED $120 THIS MONTH. I’M CRYING. I NEED A HUG.

Jay Wallace

Oh here we go again. Another ‘generic drug outrage’ article. Newsflash: the free market works. If you can’t afford it, don’t take it. Or better yet, move to Canada where they ration care and wait 6 months for a knee replacement.

And ‘transparency laws’? Please. That’s just socialism with a side of virtue signaling. You think forcing pharmacies to post prices will fix anything? Nah. It’ll just make them raise their prices to cover compliance costs.

Also, GoodRx? That’s just another app trying to monetize your desperation. You’re not saving money-you’re just feeding another tech bro’s startup.

And don’t even get me started on ‘Cost Plus Drug Co.’ It’s a gimmick. They’re not selling drugs-they’re selling the illusion of fairness. The system’s broken? Fix it by not being a victim. Get a job. Get insurance. Stop whining.

Rashmi Mohapatra

India sells generic drugs for $1. You people are so dumb. We have 100% generic metformin for 2 rupees. 2. Rupees. That’s 2 cents. You pay $60? You got scammed by capitalism. You think you’re living in a democracy? Nah. You’re living in a pharmacy cartel.

Why don’t you just order from India? It’s legal if you buy less than 3 months supply. I do it. My mom’s BP meds cost me $5 shipped. You’re all so lazy. You want change? Do something. Don’t just cry on Reddit.

Alyssa Salazar

Let’s unpack the PBM model because this is where the real exploitation happens. PBMs don’t negotiate discounts-they negotiate rebates, and those rebates are paid by manufacturers to secure formulary placement. That means the drug with the highest rebate gets on the formulary, not the cheapest or most effective one.

And here’s the kicker: those rebates are often hidden from patients. So you think you’re getting a ‘discount’? You’re not. You’re paying a higher list price so the PBM can take a cut from the manufacturer.

It’s a perverse incentive structure. The system rewards higher prices. That’s why a $100 drug with a $40 rebate beats a $30 drug with no rebate. And you, the patient, pay the difference. This isn’t capitalism-it’s a rigged casino where the house always wins, and you’re the sucker holding the ticket.

State-level transparency laws are the only real counterweight. When you force PBMs to disclose their spreads, competition kicks in. Not because of goodwill-because greed makes them lower prices to stay competitive. That’s the only thing that works: expose the profit, and the market reacts.

And yes, cash pricing works because it bypasses the entire PBM layer. But it only works if you know what the true cost is. Which is why GoodRx is a lifeline. Not perfect. But better than being blindfolded.

Lashonda Rene

I just want to say I never thought about this before but now I’m thinking about it all the time. Like I used to just take my meds and not think about the price because I thought it was just how things are. But now I’m like, why does my neighbor pay less? Why does my pharmacy charge more? Why does insurance make it worse? It doesn’t make sense. I feel like I’m living in a weird game where the rules change every time I move. And I’m not even mad anymore, just confused. I don’t know who to trust anymore. The pharmacy? The insurance? The government? The app? I just want to take my pill and not feel like I’m being robbed every month. I’m gonna start asking for cash prices. I’m gonna check GoodRx. I’m gonna try to understand. I don’t know if it’ll fix everything but I feel like I’m not powerless anymore. That’s something, right? Maybe that’s all we can do. Just ask. Just look. Just try.

Thank you for writing this. I needed to hear it.

Andy Slack

Just a quick note: if you’re reading this and you’re on insulin or metformin or any chronic med-go to your pharmacy today. Ask for the cash price. Do it. Now.

You’ll be shocked. I promise.

And if you’re a student, a parent, a grandparent, a caregiver-share this. Don’t wait. Someone you love might be paying $80 for a pill that costs $12.

Knowledge is power. And power is cheap.

Alyssa Fisher

Replying to @3853 because I can’t believe this level of denial. You think people who can’t afford meds are lazy? Try telling that to the diabetic single mom working two jobs who still has to choose between insulin and groceries. Or the veteran on fixed income who’s paying $200 for his heart med because his plan doesn’t cover it.

‘Don’t take it’ isn’t a solution. It’s a death sentence.

And you call GoodRx a middleman? It’s a tool that cuts out the middleman. It shows you the actual price. That’s not a scam-that’s transparency.

Maybe if you spent less time mocking people who are struggling and more time fighting the system, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.