When you have diabetes, your kidneys are quietly under pressure. Most people don’t realize it until it’s too late. But there’s an early warning sign-something simple, measurable, and often ignored: albuminuria. It’s not a fancy term. It just means your urine has too much protein. And if you’re diabetic, that’s not normal. It’s your kidneys screaming for help.

What Albuminuria Really Means

Albumin is a protein your body needs. Healthy kidneys keep it in your blood. When they start to leak, albumin slips into your urine. That’s albuminuria. It’s the earliest sign that diabetes is damaging your kidneys-long before you feel tired, swollen, or notice changes in how you urinate.

The standard test is the Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio, or UACR. It’s done with a single urine sample. No special collection. No fasting. Just a cup, a strip, and a lab result.

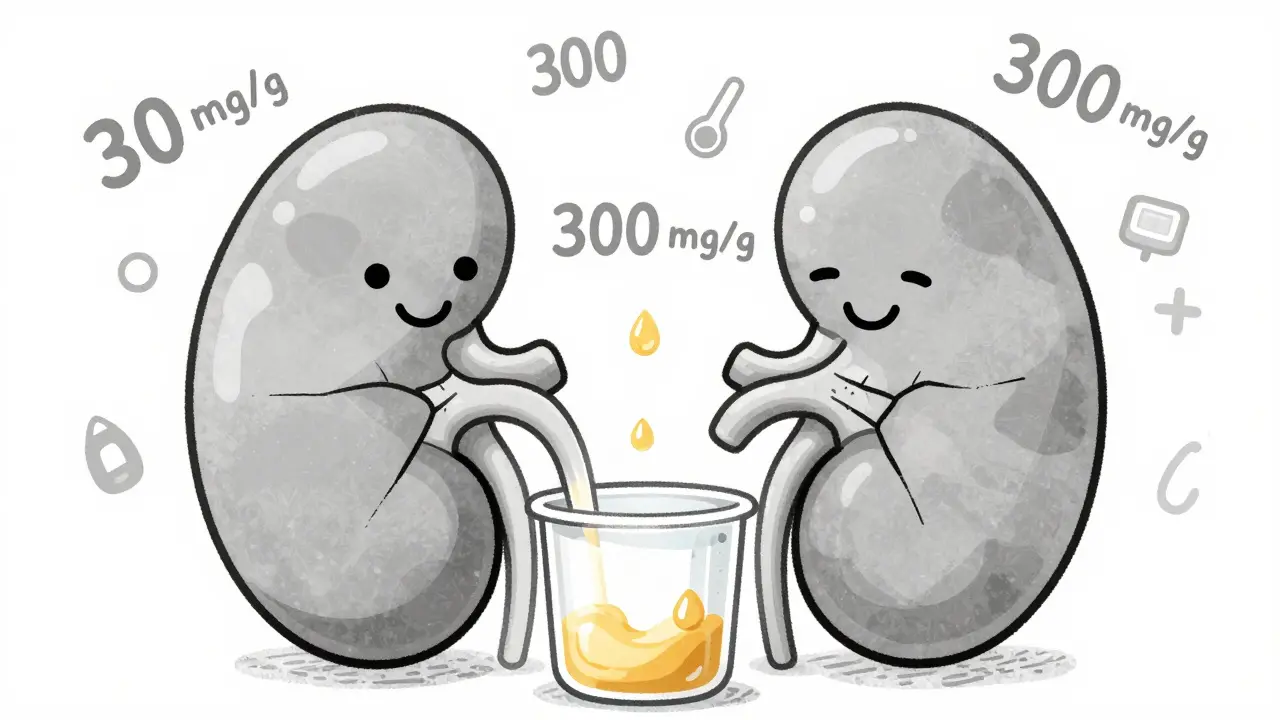

Here’s what the numbers mean:

- Normal: under 30 mg/g

- Moderately increased: 30 to 300 mg/g (used to be called microalbuminuria)

- Severely increased: over 300 mg/g (formerly macroalbuminuria)

Here’s the key point: any albumin above 30 mg/g is a problem. The old idea that "micro" was harmless is gone. Even a little leak means damage is happening. And if it’s not caught, it gets worse.

Why Timing Matters-And Why Most People Miss It

Doctors are supposed to check UACR every year for people with type 2 diabetes, starting at diagnosis. For type 1, it’s after five years. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a Class A recommendation-the strongest level of evidence-from the American Diabetes Association, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), and the National Kidney Foundation.

But here’s the hard truth: only about 60% of clinics actually do it.

Why? EHR systems don’t remind doctors. Patients forget to bring samples. Some think, "I feel fine, so why test?" But kidney damage doesn’t hurt until it’s advanced. By then, it’s often irreversible.

And it’s not just about one test. Because UACR can spike temporarily-after intense exercise, during an infection, or if your blood sugar is sky-high-you need two out of three abnormal results over 3 to 6 months to confirm true albuminuria. Skipping retesting is like ignoring a smoke alarm because it went off once.

How Tight Control Slows or Stops the Damage

Back in the 1990s, the DCCT trial changed everything. Researchers compared tight blood sugar control (HbA1c under 7%) to standard care (HbA1c around 9%) in people with type 1 diabetes. The results? A 39% drop in early kidney damage and a 54% drop in proteinuria. And here’s the kicker: those benefits lasted for decades. That’s called "metabolic memory." Your body remembers what you did for your blood sugar, even years later.

The UKPDS study showed the same pattern in type 2 diabetes. Every 1% drop in HbA1c meant a 21% lower risk of kidney disease.

Today, guidelines still say: aim for HbA1c under 7%. For younger people with no other health issues, under 6.5% is ideal. But don’t push too hard if you’re at risk of low blood sugar. Balance matters.

But sugar control alone isn’t enough. Blood pressure is just as critical.

Blood Pressure Targets: Less Is More-But Not Too Much

KDIGO recommends keeping blood pressure under 120/80 mmHg if you have severe albuminuria (over 300 mg/g). That’s aggressive. And the SPRINT trial showed it works: it cut macroalbuminuria by 39%.

But here’s the catch: lowering systolic pressure below 120 increased the risk of acute kidney injury in 1 out of every 47 people. That’s why the ADA recommends a more practical target: under 140/90 for most people with diabetic kidney disease.

The goal isn’t to crush numbers. It’s to protect your kidneys without causing harm. If you’re on medication, your doctor should adjust slowly and monitor your kidney function.

The Medications That Actually Change Outcomes

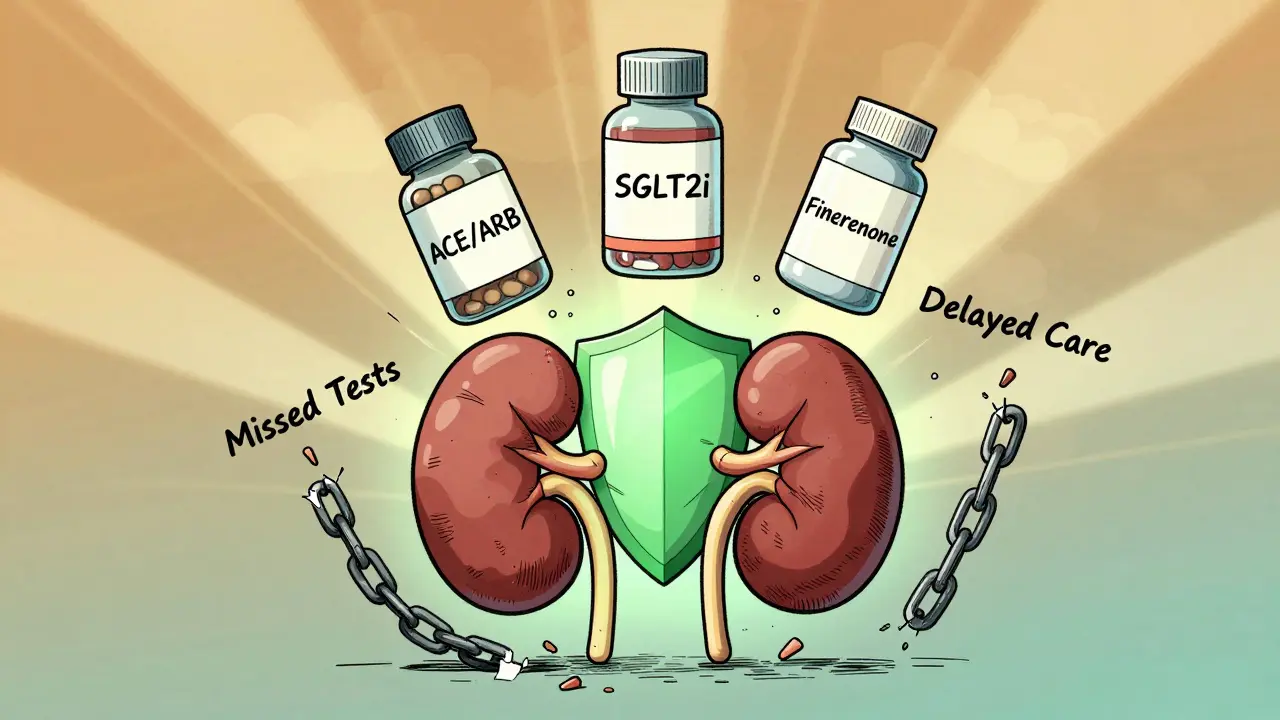

Three drug classes have proven they can slow or even reverse kidney damage in diabetic kidney disease. And they’re not optional anymore-they’re standard.

1. RAAS inhibitors (ACE inhibitors or ARBs)

The IRMA-2 trial showed that losartan, an ARB, cut the progression from moderate to severe albuminuria by 53% in people with type 2 diabetes. The rule now? Start these drugs at diagnosis if you have albuminuria-and titrate to the highest approved dose, even if your blood pressure is normal. They work on the kidney itself, not just the pressure.

2. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin, dapagliflozin)

The EMPA-KIDNEY trial in 2023 was a game-changer. In people with albuminuria over 200 mg/g, empagliflozin reduced the risk of kidney failure or death by 28%. It works by making your kidneys flush out sugar and salt. It also lowers heart failure risk. Now, guidelines say SGLT2 inhibitors should be used in nearly all diabetic kidney disease patients, regardless of HbA1c.

3. Finerenone

This newer drug, a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, was shown in 2024 to reduce albuminuria by 32% in just four months. It also slowed kidney function decline by 23% over three years-even in people already on maximum ACE/ARB therapy.

But here’s the reality: only about 29% of patients with diabetic kidney disease are on all three recommended therapies. Why? Cost. Access. Lack of awareness. And sometimes, doctors don’t know how to combine them safely.

Why So Few People Get the Right Care

It’s not that the science is missing. It’s that the system is broken.

NHANES data from 2017-2018 showed that only 12% of U.S. adults with diabetes meet all three targets: blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol. That’s not failure of willpower. That’s failure of care delivery.

Many clinics don’t have EHR alerts for UACR testing. Patients struggle to collect urine samples correctly. Some think the test is too complicated. Others are embarrassed. A 2022 survey found 41% of primary care providers didn’t fully understand how to interpret albuminuria results.

But places that fixed their systems saw results. One hospital system added automated UACR alerts to electronic records. They started using point-of-care urine tests-results in 10 minutes. They added pharmacists to the team to adjust meds. Within a year, 89% of patients reached maximum tolerated RAAS inhibitor doses.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you have diabetes, here’s your action list:

- Ask your doctor for your last UACR result. If you don’t have one from the past year, get one now.

- If your result is above 30 mg/g, ask: "Is this confirmed?" Make sure it’s been tested twice over 3-6 months.

- If you’re not on an ACE inhibitor or ARB, ask why. If you’re on one, ask if you’re on the highest safe dose.

- If you’re not on an SGLT2 inhibitor, ask if it’s right for you-even if your HbA1c is under control.

- Check your blood pressure at home. Write it down. Bring it to your visits.

- Don’t wait for symptoms. Kidneys don’t hurt until it’s late.

And if you’re a caregiver or family member: help remind them. Bring the urine cup. Call the pharmacy. Ask the questions. This isn’t just about numbers. It’s about keeping someone’s body working for years to come.

The Bigger Picture: What’s Possible

The 2024 ADA/KDIGO consensus report says that if we fully applied current guidelines, we could prevent 1.2 million new cases of diabetic kidney disease in the U.S. by 2030. That’s 37% fewer people needing dialysis. And $14.8 billion saved in healthcare costs.

It’s not science fiction. It’s data. It’s proven drugs. It’s simple tests. It’s consistency.

The problem isn’t that we don’t know how to stop it. The problem is that we don’t do it-often enough, early enough, or together enough.

Your kidneys don’t need miracles. They need attention. And the moment you find albumin in your urine, that’s your chance to act. Before the damage spreads. Before it’s too late.

Comments

Colin Pierce

Just got my UACR back last week-42 mg/g. Felt like a punch in the gut, but honestly? This post saved me. I didn’t even know albuminuria was a thing. My doc never brought it up. I’m scheduling a follow-up tomorrow to ask about ARBs and SGLT2 inhibitors. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

Kevin Kennett

Let’s be real-most doctors are asleep at the wheel. I’ve had type 2 for 12 years and never got a UACR test until I demanded it. Now I’m on empagliflozin and losartan. My numbers are better than my ex’s social media presence. If your doc isn’t pushing these meds, find a new one. Your kidneys aren’t optional.

Jess Bevis

Test. Confirm. Treat. That’s it.

Howard Esakov

Wow. Finally, someone who understands that this isn’t just "diabetes management"-it’s precision nephrology. I mean, have you seen the data on finerenone? 32% albuminuria reduction in 4 months? 😎 This is why I stopped trusting generalists. Endocrinologists with nephrology certs only, please. 🧠🩺

Kathy Scaman

I showed this to my dad-he’s had diabetes since 2010. He’s been ignoring his kidneys like they’re his ex’s texts. Now he’s actually asking his doctor about the urine test. Small win. I’m proud. 🥹

Anna Lou Chen

Albuminuria? A mere symptom of the biopolitical fragmentation of renal autonomy under late-stage metabolic capitalism. The real crisis isn’t protein leakage-it’s the commodification of biomarkers into surveillance tools for the glycemic proletariat. Who profits from the UACR? The lab? The pharma? The EHR vendor? We must deconstruct the diagnostic gaze.

Lance Long

Hey, if you’re reading this and you’ve got diabetes-don’t panic. You’re not behind. You’re just getting started. I was in your shoes two years ago. Now I’m on SGLT2, my BP’s under control, and I actually feel better. It’s not magic. It’s consistency. One step. One test. One pill at a time. You got this.

fiona vaz

My mom’s diabetic and her UACR was 89 last year. We pushed for the ARB and she’s been on it for 10 months now-down to 22. No side effects. She says she feels more energy. It’s not glamorous, but this stuff works. Thank you for the clear breakdown.

Sue Latham

Ugh. I’m so tired of people acting like this is new info. I’ve been on ARBs since 2017. SGLT2 since 2020. Finerenone? I’m waiting for my insurance to stop being a nightmare. But you? You’re probably still using metformin and hoping for the best. 🙄

John Rose

While the clinical evidence for early intervention is robust, one must consider the heterogeneity of patient populations. The DCCT and UKPDS cohorts were highly selected. Real-world adherence, comorbidities, and socioeconomic factors significantly modulate outcomes. Thus, while the guidelines are sound, implementation requires nuanced, individualized care pathways.

Lexi Karuzis

ALBUMINURIA IS A GOVERNMENT PLOY TO GET YOU ON DRUGS!!! THE KIDNEYS DON'T LEAK-THEY'RE JUST "STRESSED" BY THE FLUORIDE IN THE WATER AND THE 5G TOWERS!!! THEY WANT YOU TO THINK YOU NEED SGLT2 INHIBITORS SO THEY CAN SELL YOU MORE MEDS!!! I DID A RESEARCH ON REDDIT AND FOUND A VIDEO WHERE A DOCTOR SAID THIS WAS A SCAM!!!

Mark Alan

USA IS THE ONLY COUNTRY THAT DOES THIS RIGHT. CANADA? THEY WAIT TILL KIDNEYS FALL OUT. EUROPE? THEY JUST GIVE YOU TEA AND TELL YOU TO "RELAX". I’M ON ALL THREE DRUGS. MY KIDNEYS ARE FINE. I’M A HERO. 🇺🇸💪🔥

matthew martin

My brother’s a nurse at a rural clinic. They just got a point-of-care UACR machine. Used to take 3 weeks for results. Now? 10 minutes. Patients are actually getting treated. One guy, 62, had been ignoring his numbers for 7 years. Got his UACR back at 380. Started ARB + SGLT2. Two months later? Down to 90. He cried. Said he didn’t think he’d live to see his granddaughter graduate. Now he’s walking every morning. That’s the stuff.

Jeffrey Carroll

While the therapeutic efficacy of RAAS inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors is well-documented, the long-term cost-effectiveness of triple therapy in low-resource settings remains underexplored. A pragmatic approach may require tiered implementation based on regional infrastructure, rather than universal application.

doug b

Just tell your doctor: "I want the urine test. I want the ACE/ARB. I want the SGLT2. Don’t give me excuses. My kidneys aren’t a suggestion." It’s that simple. You don’t need to be a genius. You just need to show up.