Stent Thrombosis Risk Calculator

Enter your details and click calculate to see your risk level

Risk Factors Explained

Obesity Impact

Higher BMI increases inflammation and clotting factors, raising stent thrombosis risk.

Heart Disease History

Previous heart conditions increase overall cardiovascular risk.

Smoking

Smoking damages blood vessels and increases clotting tendency.

When a heart attack or peripheral artery disease forces a doctor to place a metal mesh inside a narrowed artery, the goal is simple: keep blood flowing. Yet a hidden danger can creep in-clots forming on that mesh. Recent research shows that obesity isn’t just a weight issue; it reshapes the blood’s chemistry and the artery wall, turning a life‑saving stent into a ticking time bomb.

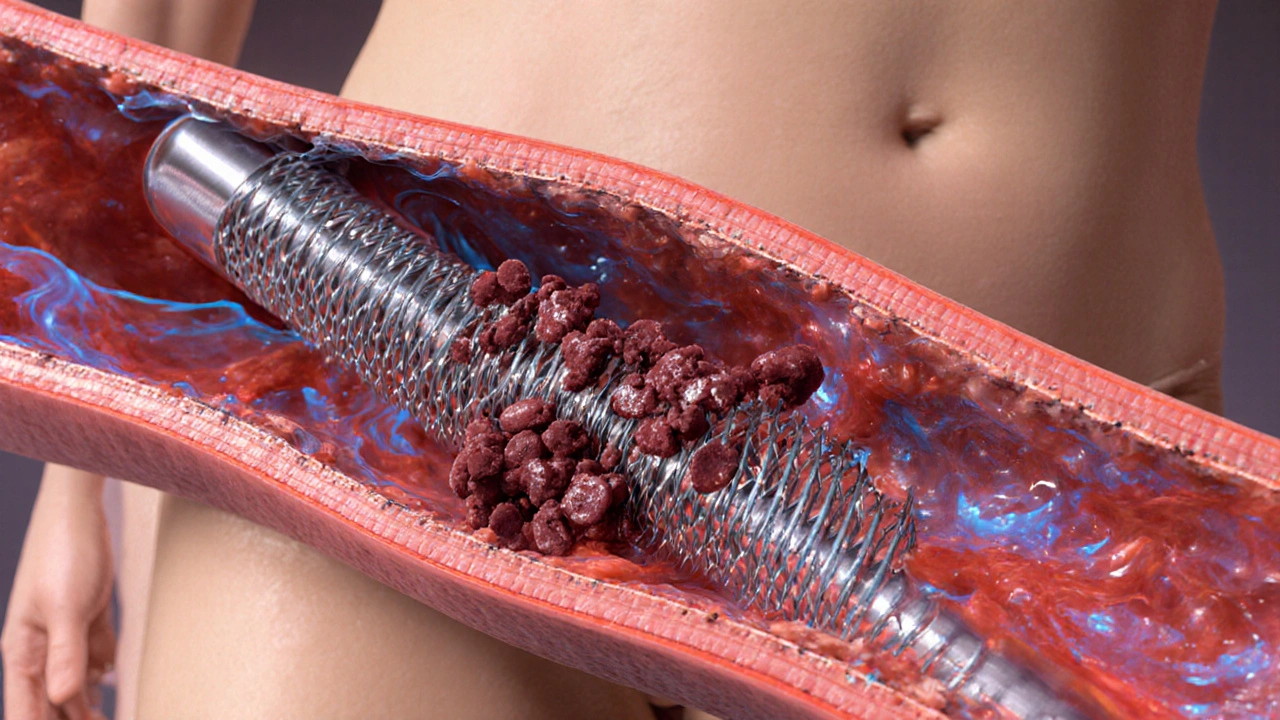

What a Stent Is and Why Clots Matter

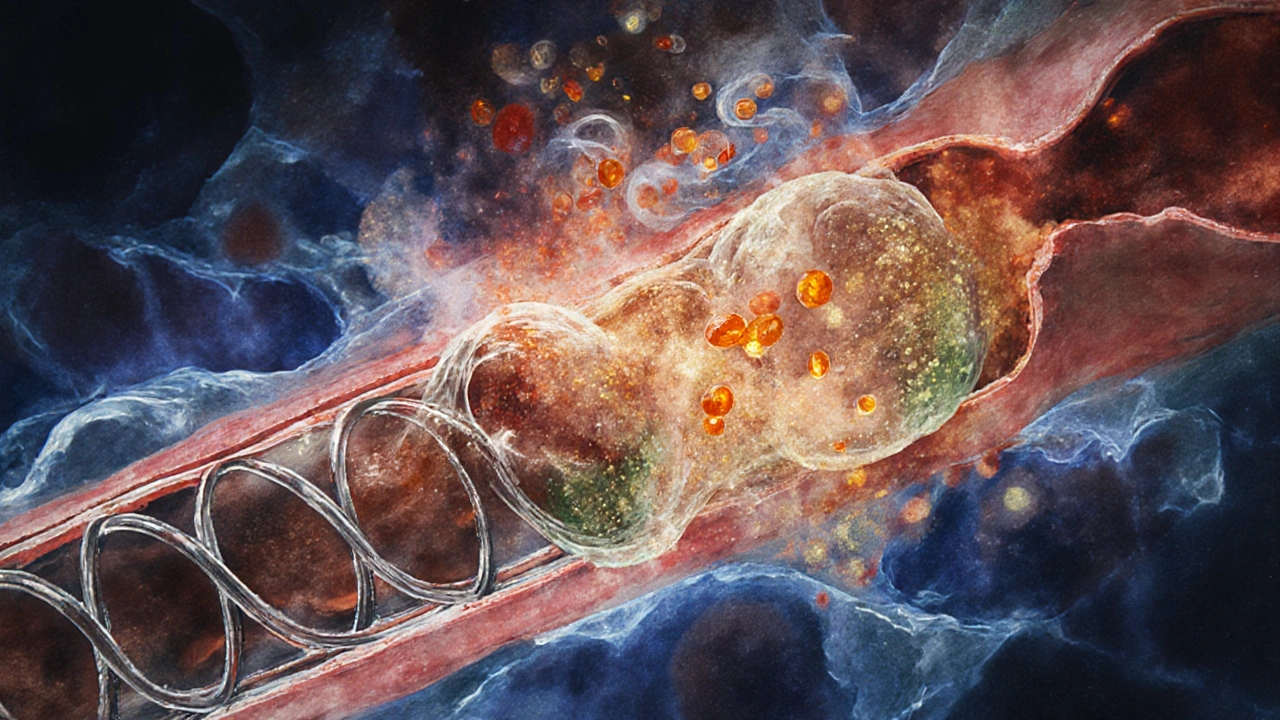

Stent is a tiny tube‑like scaffold, usually made of stainless steel or cobalt‑chrome, that doctors expand inside a blocked artery to hold it open. The device itself is inert, but once implanted it becomes a foreign surface that the bloodstream constantly surveys. If platelets and clotting proteins stick to the stent, a blood clot can grow, narrowing the passage again-a phenomenon called stent thrombosis. This event can cause a heart attack, stroke, or limb‑loss depending on the vessel involved.

Obesity’s Molecular Footprint on Blood and Vessels

Obesity is a chronic condition characterized by excess adipose tissue, typically measured by body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m². That extra tissue isn’t just stored fat; it’s an active endocrine organ releasing hormones, inflammatory cytokines, and free fatty acids. These messengers create three key problems for stent patency:

- Inflammation spikes, driving higher levels of C‑reactive protein and interleukin‑6, which activate platelets.

- Endothelial dysfunction reduces nitric oxide production, weakening the vessel’s natural anti‑clot lining.

- Hypercoagulability raises fibrinogen and clotting factor VII, making the blood more prone to clot formation.

All three create a perfect storm for a clot to latch onto a newly placed stent.

Clinical Evidence Linking Obesity to Stent Thrombosis

Large registries and meta‑analyses from the past five years consistently point to a higher incidence of stent thrombosis among patients with BMI ≥30. One 2023 pooled analysis of 12,000 coronary stent patients found a 1.8‑fold increase in early (<30days) thrombosis for obese individuals compared with those in the normal‑weight range. Similar trends appear in peripheral arterial disease (PAD) studies, where obese patients experience a 2‑times higher rate of femoral‑or‑popliteal stent occlusion.

These findings hold even after adjusting for traditional risk factors like diabetes, smoking, and hypertension, underscoring obesity’s independent contribution.

Risk Assessment: BMI Categories vs. Stent Thrombosis Rates

| BMI (kg/m²) | Category | Early thrombosis | Late thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | Normal weight | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| 25‑29.9 | Overweight | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 30‑34.9 | Obesity class I | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| 35‑39.9 | Obesity class II | 6.7 | 5.1 |

| ≥40 | Obesity class III | 9.2 | 7.8 |

Numbers vary by study, but the upward trend is unmistakable. The higher the BMI, the steeper the climb in both early and late thrombosis.

Prevention Strategies Tailored for Obese Patients

Because the mechanisms are multi‑factorial, a layered approach works best.

- Weight reduction. Even a 5‑10% drop in body weight improves inflammatory markers and platelet reactivity. Structured lifestyle programs-combining dietary counseling, moderate‑intensity exercise (150minutes/week), and behavioral coaching-have shown a 30% reduction in clot formation risk within six months.

- Optimized antiplatelet therapy. Antiplatelet therapy (usually aspirin+a P2Y12 inhibitor) is standard after stent placement. In obese patients, studies suggest higher doses of clopidogrel or switching to ticagrelor can counteract the heightened platelet activation.

- Addressing comorbidities. Controlling diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia reduces the additive clot risk. Statins, for example, lower fibrinogen levels beyond their cholesterol‑lowering effect.

- Monitoring inflammatory status. Periodic measurement of C‑reactive protein helps identify patients slipping back into a pro‑inflammatory state, prompting early therapeutic tweaks.

- Device selection. Newer drug‑eluting stents (DES) releasing antiproliferative agents like everolimus have shown lower thrombosis rates in high‑BMI cohorts compared with first‑generation DES.

Managing an Occluded Stent in an Obese Patient

If a clot does form, prompt action is critical. The standard emergency pathway includes:

- Immediate high‑dose intravenous antithrombotic (e.g., unfractionated heparin).

- Urgent coronary or peripheral angiography to assess the blockage.

- Possible thrombus aspiration or balloon angioplasty to restore flow.

- Re‑evaluation of antiplatelet regimen-often escalating to a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor.

Long‑term, the patient should be enrolled in an intensive cardiac rehabilitation program that emphasizes weight loss, aerobic conditioning, and nutrition counseling.

Practical Checklist for Clinicians and Patients

- Before stent placement:

- Calculate BMI and categorize risk.

- Order baseline inflammatory markers (CRP, IL‑6).

- Discuss weight‑loss goals and refer to a dietitian.

- During peri‑procedural care:

- Choose a DES with proven low thrombosis rates in obese populations.

- Load with aspirin 325mg and a potent P2Y12 inhibitor (ticagrelor 180mg).

- Post‑procedure follow‑up (1‑month, 6‑months, 12‑months):

- Re‑measure BMI; aim for ≥5% reduction by 6months.

- Repeat CRP; if still elevated, consider adding low‑dose colchicine.

- Assess medication adherence; adjust antiplatelet dosing if needed.

- If symptoms of thrombosis appear:

- Call emergency services immediately.

- Provide recent medication list and BMI to the responding team.

Bottom Line: Weight Matters for Stent Success

Obesity adds a biochemical edge to the already delicate balance of clot prevention after a stent is placed. By recognizing the extra risk, adjusting medication, and actively pursuing weight loss, patients and clinicians can dramatically cut the odds of a dangerous clot.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does losing just a few pounds lower the risk of stent clotting?

Yes. Research shows that a 5‑10% body‑weight reduction can decrease inflammatory markers and platelet activity enough to lower early stent thrombosis risk by roughly one‑third.

Are there stents specifically designed for obese patients?

While no stent is marketed exclusively for obesity, newer generation drug‑eluting stents (e.g., everolimus‑eluting) have demonstrated lower clot rates in high‑BMI groups compared to older models.

Should antiplatelet doses be increased in obese patients?

Many cardiologists opt for higher loading doses or more potent agents (ticagrelor or prasugrel) in patients with BMI≥30kg/m², especially if they have additional pro‑thrombotic factors.

Can regular exercise alone protect my stent?

Exercise improves endothelial function and reduces inflammation, but it works best when paired with weight loss, optimal medication, and control of other risk factors like diabetes.

What symptoms signal a stent clot?

Sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, or limb pain (for peripheral stents) can indicate thrombosis. Seek emergency care immediately.

Comments

Earlene Kalman

Obesity just makes stents a nightmare. The data is obvious.

Leon Wood

Whoa, hold up! While obesity does raise clot risk, it's not a death sentence. The body’s inflammatory response can be managed with lifestyle tweaks and proper medication. Think of it like tuning a car-you adjust the fuel, the oil, and the engine runs smoother. If you keep active, eat balanced meals, and stay on your doctor’s meds, the stent’s chances improve dramatically. Even the research shows that modest weight loss cuts the clotting factors in half. So don’t panic, just get moving and keep those numbers in check.

George Embaid

Great breakdown of the risk factors. It’s useful to see how BMI, age, heart history, and smoking stack up together. For anyone with a stent, monitoring these variables can help tailor preventive therapy. Remember, the calculator is a guide-not a definitive verdict.

Meg Mackenzie

Sure, the calculator looks legit, but have you considered who programmed it? Big pharma loves these tools; they push meds that keep profits up while we get side effects. The data could be cherry‑picked to scare obese patients into pricey procedures. Also, the inflammation pathways are more complex than a simple score can capture. Keep your eyes open; the system isn’t always on your side.

Matt Miller

Weight loss before a stent placement can lower your clot risk significantly.

Barry White Jr

Good point.

Henry Kim

I’ve seen patients drop a few pounds and their post‑procedure recovery was smoother. It’s a small step that makes a big difference.

Neha Bharti

Remember, every healthy habit you add chips away at the clot risk. Even simple walks, staying hydrated, and regular check‑ups build a stronger vascular system.

Samantha Patrick

Thx for the tip! I’ll try to jus drink more water and get out for a walk each day.

Ryan Wilson

Sure, because everyone has the time to overhaul their diet and exercise routine after getting a stent. Some of us are juggling work, kids, and bills, not a personal health retreat.

EDDY RODRIGUEZ

Hey, I hear you, the demands on our time can feel overwhelming.

But the reality is that the body doesn’t care how busy we are-it still responds to the chemistry inside.

When you carry extra weight, your blood vessels become more prone to inflammation.

That inflammation releases clotting factors that can latch onto the stent metal.

Even a modest 5‑10% reduction in weight can shift those numbers in your favor.

Think of it like clearing debris from a pipe; less blockage means smoother flow.

Regular movement, even a short walk after meals, keeps blood circulating and reduces stasis.

Staying hydrated helps the blood stay thin enough to glide past the stent without clumping.

Consistent medication adherence is another pillar that works hand‑in‑hand with lifestyle changes.

Your doctor can adjust antiplatelet therapy based on how your risk profile evolves.

If you’re worried about time, start with micro‑habits: a 10‑minute stretch in the morning or swapping a sugary snack for a fruit.

Over weeks, those tiny shifts compound into measurable health gains.

You’ll likely notice better energy levels, easier breathing, and lower blood pressure.

All of those outcomes feed back into a lower clot risk around the stent.

So while the calendar is packed, carving out a few minutes for yourself is an investment that pays dividends.

In the end, your heart and the stent will thank you for the extra care you give them.

Christopher Pichler

Wow, what a groundbreaking revelation-weight loss, hydration, micro‑habits. As if the whole field of interventional cardiology was hidden behind a veil of mystique. Thank you for distilling decades of peer‑reviewed research into a bullet‑point checklist. I’ll be sure to publish a meta‑analysis on “How Eating Salad Saves Stent Longevity.”