Imagine taking a pill that’s supposed to help you feel better - but instead, it makes you sick. Or worse, it does nothing at all. This isn’t rare. Around 6.7% of all hospital admissions in the U.S. are caused by bad reactions to medications. And for many people, it’s not because they took too much or mixed drugs wrong. It’s because their body processes that drug differently than the average person. That’s where pharmacogenomics comes in.

What Is Pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect how your body responds to drugs. It’s not about predicting if you’ll get cancer or heart disease. It’s about answering a simpler, more immediate question: Will this medication work for me - or hurt me?

Every person’s DNA is unique. That includes the genes that code for enzymes in your liver - the ones that break down medicines. Some people have versions of these genes that make them process drugs too fast. Others process them too slowly. A drug that works perfectly for one person might cause severe side effects or just not work at all for someone else. Pharmacogenomics looks at these differences before you even take the pill.

The field took off after the Human Genome Project finished in 2003, but the real shift came with the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC). Founded in 2009, CPIC brings together scientists and doctors to create clear, evidence-based guidelines for using genetic test results in real-world prescribing. As of 2023, they’ve published guidelines for 42 gene-drug pairs. That means if your doctor knows your genetic profile, they can pick the right drug and the right dose - not guess.

How Is Genetic Testing Done?

Getting tested is simple. No needles, no hospital visit. Most tests use a saliva sample, a cheek swab, or sometimes a small blood draw. The sample goes to a lab that looks at specific genes known to affect drug metabolism. The most common ones are CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9. These genes control how your body handles about 70-80% of the medications that have known genetic interactions.

For example, CYP2D6 breaks down antidepressants like fluoxetine, painkillers like codeine, and beta-blockers like metoprolol. If you’re a “poor metabolizer,” codeine won’t turn into its active form - you’ll get no pain relief. If you’re an “ultra-rapid metabolizer,” codeine turns into morphine too fast - you could overdose on a standard dose. That’s not a theory. It’s happened. In 2022, a Canadian study found that 22% of patients on antidepressants or antipsychotics had their medication changed after genetic testing. One Reddit user switched from codeine to tramadol after years of severe nausea - and it vanished overnight.

Testing isn’t just about metabolism. Some genes warn you about dangerous side effects. The HLA-B*15:02 variant, for instance, increases the risk of a life-threatening skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson Syndrome by 1,000 times if you take carbamazepine (an epilepsy and bipolar drug). The FDA now recommends testing for this variant before prescribing it - especially for people of Asian descent.

Where Does It Work Best?

Pharmacogenomics isn’t magic. It doesn’t help with every drug. Right now, only about 15-20% of commonly prescribed medications have strong genetic guidance. But in some areas, the impact is undeniable.

In psychiatry, studies show patients whose treatment is guided by genetic testing have a 30.8% remission rate for depression - compared to just 18.5% for those on standard care. That’s a big jump. One Mayo Clinic patient had 15 years of treatment-resistant depression. Genetic testing revealed she was an ultra-rapid metabolizer of paroxetine. Her doctor switched her to bupropion. Within eight weeks, her symptoms disappeared.

In oncology, genetic testing identifies tumor mutations that make targeted therapies effective. Foundation Medicine’s study of over 25,000 cancer patients found that 15.3% had actionable mutations - but only 8.5% actually got the matched drug. Why? Insurance denials and slow referrals. Still, for those who do get matched, survival rates improve dramatically.

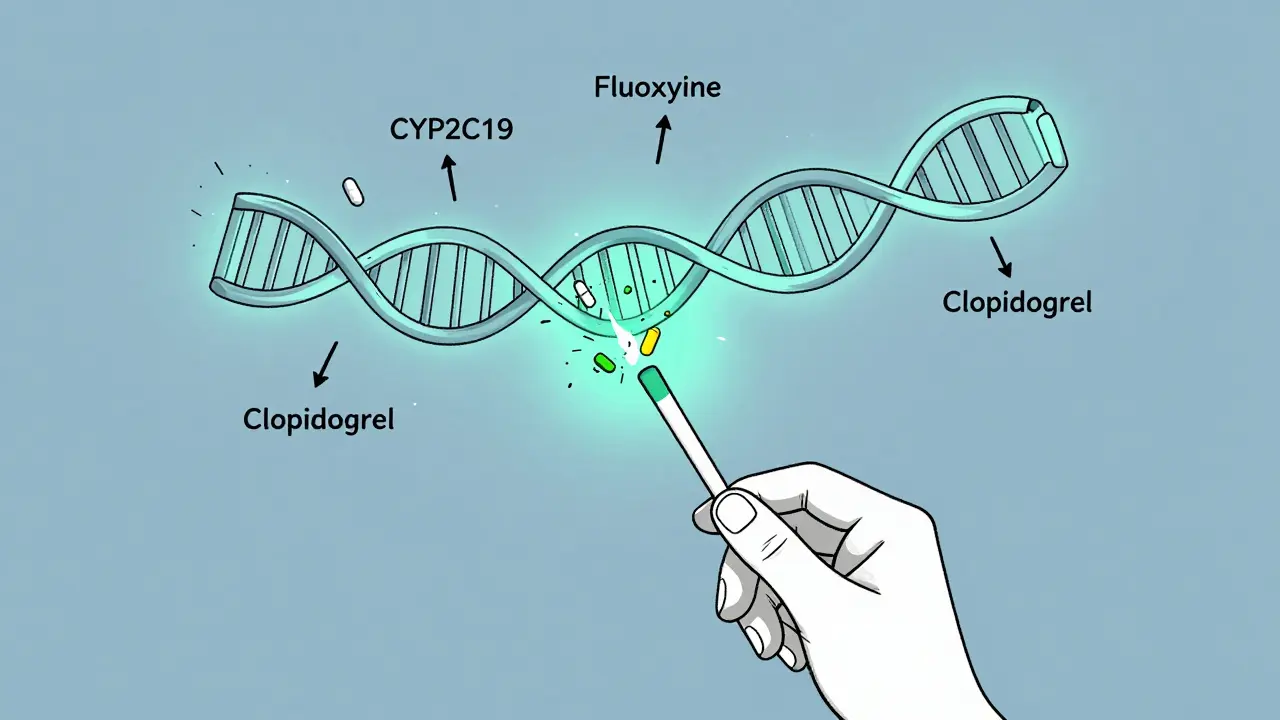

In cardiology, the story is more complicated. A major trial called TAILOR-PCI looked at whether testing for CYP2C19 variants before giving clopidogrel (a blood thinner after stents) improved outcomes. The results? No significant difference. That surprised many. But newer trials like TAILOR-PCI2 - now enrolling 6,000 patients across 15 countries - aim to settle the debate with better data.

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting Tested?

If it’s so helpful, why isn’t this routine? Three big reasons: evidence gaps, integration hurdles, and cost.

First, not all gene-drug pairs have strong proof. CPIC has guidelines for 42 pairs - but there are 118 genes that could matter. Only 28 of them are even mentioned in FDA drug labels. For many drugs, the data is still emerging.

Second, most hospitals don’t have the systems to use the results. A 2022 study found only 37% of healthcare systems had successfully integrated pharmacogenomic data into their electronic records. That means even if you get tested, your doctor might not see the results - or know what to do with them. Pharmacists need training too. One survey found 68% of pharmacists felt unprepared to interpret complex results, especially for genes like CYP2D6 that have dozens of variants.

Third, insurance coverage is patchy. In the U.S., 89% of commercial plans cover PGx testing for cancer drugs. For psychiatric drugs? Only 47%. In Australia, Medicare doesn’t yet subsidize routine PGx testing, though some private insurers are starting to include it.

What’s Changing Now?

Things are moving fast. The FDA is pushing for mandatory PGx testing on 12 new drugs by 2025 - including statins, SSRIs, and warfarin. PharmGKB predicts that by 2027, half of commonly prescribed drugs will have actionable genetic guidance - up from 15-20% today.

Big research projects are filling the gaps. The NIH’s All of Us program has collected genetic data from over 3.5 million Americans, including 100 pharmacogenes. For the first time, we’re getting data from non-European populations - which matters because gene variants differ across ethnic groups. Right now, 78% of PGx studies are based on people of European descent. That’s a problem when prescribing for diverse populations.

Companies are scaling up too. Thermo Fisher Scientific, Myriad Genetics, and Invitae dominate the market. Tests cost between $200 and $500 out-of-pocket - but prices are dropping as demand rises. The global market is expected to hit $23.8 billion by 2030.

What Should You Do?

You don’t need to get tested right now - unless you’re on a drug with known genetic risks. But if you’ve had bad reactions to medications, or if multiple drugs have failed you, it’s worth asking your doctor.

Start with these questions:

- Have I had serious side effects from a medication that others didn’t?

- Have I tried several antidepressants or painkillers that didn’t work?

- Am I taking a drug like clopidogrel, carbamazepine, codeine, or warfarin?

If you answered yes to any of these, pharmacogenomics might help. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Ask if they use CPIC guidelines. Ask if they’ve seen results from testing. Don’t be afraid to push for it - especially if you’ve been stuck in a cycle of trial and error.

And if you’ve already been tested? Share the results. Save them. Don’t let them sit on a USB drive or a PDF. Give a copy to every doctor you see. Your genes don’t change - but your medications might.

Real People, Real Results

One man in Melbourne had been on five different antidepressants over eight years. None worked. He had anxiety, insomnia, and constant fatigue. His psychiatrist finally suggested a PGx test. The results showed he was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer - meaning his body couldn’t break down most SSRIs properly. He was prescribed a drug that didn’t rely on that enzyme. Within six weeks, his sleep improved. His anxiety dropped. He stopped feeling like he was running on empty.

Another woman in Sydney took codeine after surgery and ended up in the ER with respiratory depression. Her daughter, a medical student, pushed for genetic testing. Turns out she was an ultra-rapid metabolizer. Codeine turned into morphine too fast. Her next painkiller? A non-opioid option. No more hospital visits.

These aren’t outliers. They’re the future.

Is pharmacogenomic testing covered by insurance in Australia?

Currently, Medicare does not subsidize routine pharmacogenomic testing in Australia. Some private health insurers are beginning to cover it for specific cases, like psychiatric medications or cancer treatment, but coverage varies widely. Most people pay out-of-pocket, with tests ranging from $200 to $500. If you’re on a high-risk medication, ask your doctor if your insurer will approve it as a medical necessity.

Can I use a direct-to-consumer test like 23andMe for pharmacogenomics?

Some direct-to-consumer tests, including 23andMe, report on a few pharmacogenomic variants like CYP2C19 and CYP2D6. But they’re not designed for clinical use. They don’t test all relevant variants, don’t interpret results in context, and aren’t validated for medical decisions. A 2023 Reddit user reported their 23andMe result didn’t change their psychiatrist’s approach - because the evidence wasn’t strong enough. For reliable results, use a test ordered by a healthcare provider that follows CPIC guidelines.

How long does it take to get results from a pharmacogenomic test?

Most clinical labs deliver results in 7 to 14 days. Some faster services offer results in 5 days. The turnaround time depends on the lab, the number of genes tested, and whether the test is ordered through a hospital or private provider. Once you have the results, your doctor or pharmacist should review them with you - ideally before starting a new medication.

Are there any risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is zero - it’s just a saliva swab or blood draw. The bigger risks are psychological and practical. You might learn you have a genetic variant that increases your risk for a bad reaction - which could cause anxiety. You might also find out your insurance won’t cover the recommended drug, or your doctor doesn’t know how to act on the results. That’s why testing should always be paired with genetic counseling or clinical support.

Will my genetic data be shared with my employer or insurer?

In Australia, the Genetic Discrimination Act 2021 prohibits health insurers and employers from requiring or using genetic test results to deny coverage or employment. Your pharmacogenomic data is protected under the same privacy laws as your medical records. Labs are required to de-identify data and store it securely. But always ask how your data will be used before testing - and confirm whether it will be stored for future research.

How often do I need to be tested?

You only need to be tested once. Your genes don’t change. A pharmacogenomic test result from 10 years ago is still valid today. The challenge isn’t repeating the test - it’s making sure your doctors know the results. Keep a copy in your personal health record and share it with every new provider. Some hospitals now store PGx results in electronic health records permanently - but not all do.

Comments

Marian Gilan

so u know what's REALLY happening? big pharma HATES this stuff. they make more money when you keep trying drugs that don't work & keep coming back. genetic testing? nahhh... we'd rather you stay addicted to side effects & copays. they've been burying this since the 90s. #corporatecontrol

Conor Murphy

This is actually life-changing stuff 😊 I had a cousin who tried 7 antidepressants before a PGx test showed she was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Switched to mirtazapine and she's been stable for 3 years now. So glad this is getting attention!

Conor Flannelly

It's fascinating how biology is just... personalized code. We treat meds like one-size-fits-all software, but our bodies are more like custom-built machines with unique firmware. The fact that we're only now starting to read the manual properly feels almost embarrassing. We've been guessing at human chemistry for a century while ignoring the manual written in DNA. We need to stop treating biology like a black box.

Patrick Merrell

I'm not buying it. This is just another way for corporations to profit off your DNA. They'll charge you $500 to tell you what you already know: 'this drug made you sick'. And don't even get me started on data privacy. They'll sell your genes to advertisers next. You think your insurance won't use this to deny you coverage? Think again.

Napoleon Huere

I've been waiting for this to go mainstream for years. The real tragedy isn't that it's not used-it's that it's treated like a luxury. This isn't sci-fi. It's pharmacology 101. If we can map Mars, why are we still guessing how drugs work in humans? We're not in the dark ages anymore. Time to stop pretending we are.

Shweta Deshpande

Oh my gosh, I just read this and I'm crying a little 😭 I’ve been on 11 different meds for anxiety over 12 years-some made me suicidal, others just made me zombie-like. My psychiatrist finally ordered a test last year and we found I’m a CYP2C19 ultra-rapid metabolizer. Switched to sertraline + low-dose lamotrigine and suddenly I’m sleeping, laughing, even going outside again. I wish I’d known this 10 years ago. Please, if you’ve struggled like I have-ask for this. It’s not magic, but it’s the closest thing to a lifeline I’ve ever found.

Robin Van Emous

I work in a clinic and we started using PGx last year. It's not perfect, but it's changed how we treat patients. One guy came in with chronic pain and had been on opioids for 8 years. Test showed he couldn't metabolize codeine at all. We switched him to gabapentin + physical therapy. No more pills. No more ER visits. He cried when he told us he hadn't slept through the night in 5 years. This isn't just science-it's human.

rasna saha

I'm from India and we don't have access to this yet, but I'm so hopeful! My mom had a bad reaction to clopidogrel after her stent and they just kept giving her more. No one thought to test her genes. I'm studying biotech now so I can help make this accessible here. We need this everywhere-not just in rich countries.

Ashley Porter

CYP2D6 is the MVP of PGx. It handles 25% of all prescriptions. Ultra-rapid metabolizers get opioid toxicity. Poor metabolizers get zero efficacy. The fact that we still prescribe codeine without screening is wild. It's like giving a car key to someone who doesn't know how to drive. The FDA’s moving slow, but the data’s undeniable.

shivam utkresth

Bro, imagine if your phone came with no manual and you just kept downloading apps hoping one wouldn’t crash it. That’s what medicine is right now. PGx is the damn user guide. And yeah, 23andMe’s useless for clinical use-but it’s a wake-up call. My cousin got flagged for CYP2C19*2 on 23andMe, went to her doc, got switched from citalopram to escitalopram, and suddenly she wasn’t feeling like a zombie anymore. Tech’s not perfect, but it’s the first step.

John Wippler

This is the future and it’s beautiful. We’re moving from trial-and-error medicine to precision medicine. Imagine a world where your doctor doesn’t guess-they know. Where side effects aren’t ‘bad luck’ but predictable, preventable outcomes. We’re not just treating diseases anymore-we’re tuning the human instrument. And yeah, it’s gonna take time, funding, training... but this? This is the kind of progress that saves lives, not just profits.

Ryan W

America spends billions on this nonsense while our hospitals can’t afford basic antibiotics. We’ve got people dying because they can’t get insulin, but we’re running genetic tests so someone doesn’t get nauseous on Zoloft? This is what happens when you let tech bros run healthcare. Fix the system first. Then worry about your CYP2D6 status.