Most people think a drug patent lasts 20 years. That’s what you hear in the news, what you read on packaging, and what your doctor might casually mention. But if you’re waiting for a cheaper generic version to come out, that 20-year number is misleading. In reality, most brand-name drugs lose market exclusivity in 7 to 12 years-not 20. Why? Because the clock starts ticking long before the drug even hits the pharmacy shelf.

The 20-Year Clock Starts at Filing, Not Approval

Under U.S. law, drug patents are granted for 20 years from the date the application is first filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). That’s straightforward on paper. But here’s the catch: drug development takes years. On average, it takes 8 to 10 years just to go from initial patent filing to FDA approval. That means half-or more-of the patent term is already gone before the drug can be sold.

Take a drug like Humira (adalimumab). Its original patent was filed in 1997. But it didn’t get FDA approval until 2002. That gave it only about 15 years of potential exclusivity, even before any extensions. And even then, it didn’t get the full 15. Multiple lawsuits, patent challenges, and regulatory exclusivities shifted the timeline. The first biosimilar didn’t launch until 2023-21 years after the original filing, but only 21 years because of layered protections, not because the patent lasted longer.

Patent Term Extension: The 5-Year Lifeline

Enter the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. This law created Patent Term Extension (PTE) to make up for time lost during FDA review. If a drug company can prove the FDA took too long to approve their product, they can get up to five extra years of patent life. But there’s a catch: the total market exclusivity-patent plus regulatory time-can’t exceed 14 years from the date of FDA approval.

For example, if a drug is approved in 2020 and the patent was filed in 2010, the patent would normally expire in 2030. But if the FDA took 7 years to approve it, the company could apply for a 5-year extension, pushing the expiration to 2035. However, since the 14-year cap from approval date is stricter, the patent would expire in 2034 instead (2020 + 14 = 2034).

Here’s the kicker: you have only 60 days after FDA approval to file for this extension. Miss it, and you lose it. Many companies miss this window because they’re focused on manufacturing, not legal paperwork. And once it’s gone, there’s no second chance.

Regulatory Exclusivities: The Hidden Clocks

Patents aren’t the only thing blocking generics. The FDA gives out separate periods of market protection called regulatory exclusivities. These don’t rely on patents at all. They’re automatic, and they can stack on top of patent protection.

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years. During this time, the FDA can’t even accept a generic application. This applies to drugs with a completely new active ingredient.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients). Even if the patent expires, generics can’t enter until this period ends.

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: 3 years. For new uses, dosages, or formulations that require new clinical trials. This doesn’t block the original generic, but it blocks competitors trying to copy the new version.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period. Companies get this bonus if they conduct pediatric studies requested by the FDA. It’s not a reward-it’s a requirement disguised as an incentive.

These exclusivities can delay generics even if the patent is invalid or expired. A drug might have its patent expire in 2025, but if it still has pediatric exclusivity running until 2026, no generic can legally launch until then. This is why some patients see price spikes right after patent expiration-insurance switches to a generic, but the generic isn’t available yet.

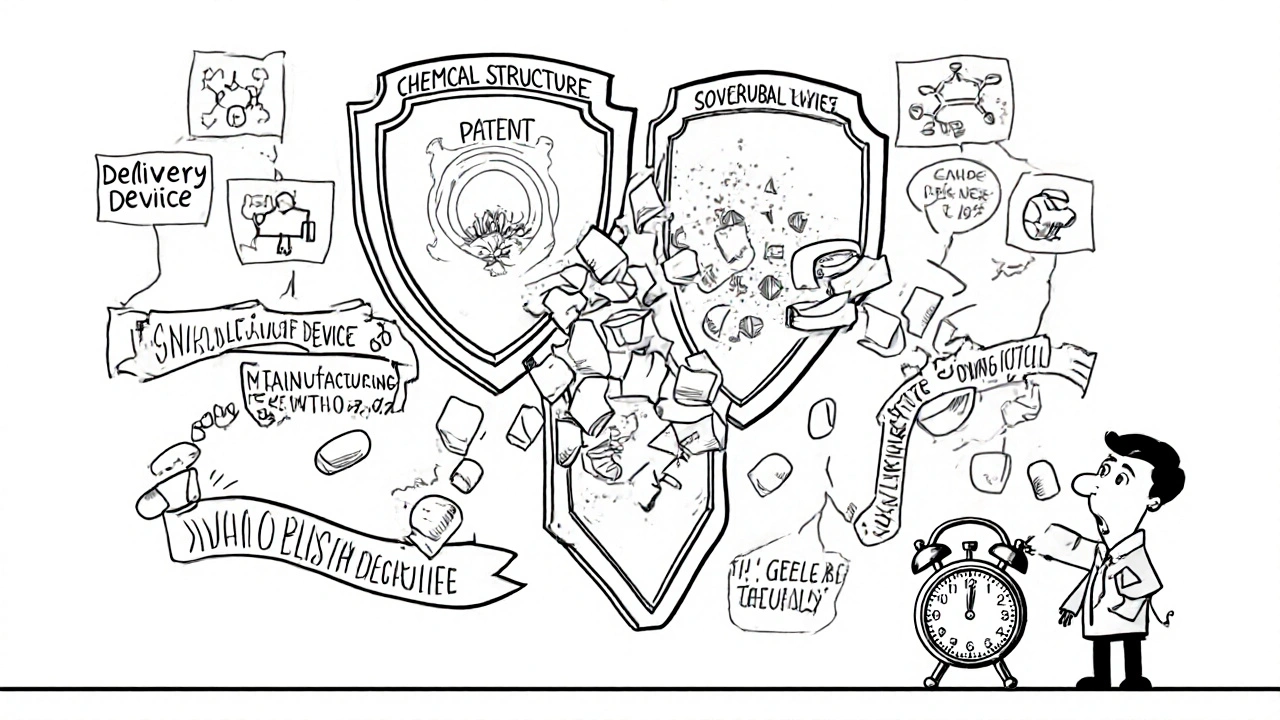

Patent Thickets and Evergreening: How Companies Stretch Protection

Big pharma doesn’t rely on one patent. They build a wall of them. This is called a “patent thicket.” A single drug like Spinraza (nusinersen) is protected by over 20 patents covering everything from the chemical structure to the delivery device to the way it’s manufactured. Each one has its own 20-year clock. Some expire in 2027. Others in 2030. The last one standing blocks generic entry.

There’s also “evergreening”-a controversial practice where companies file patents on minor changes: a new pill coating, a different dosing schedule, a new delivery pen. These aren’t new drugs. They’re tweaks. But they’re enough to trigger a new patent and delay generics by 2 to 3 years. The FTC has documented this pattern in over 60% of major drugs facing patent expiration. In some cases, these secondary patents are challenged in court and thrown out. But it takes years, and during that time, the brand-name drug keeps selling at full price.

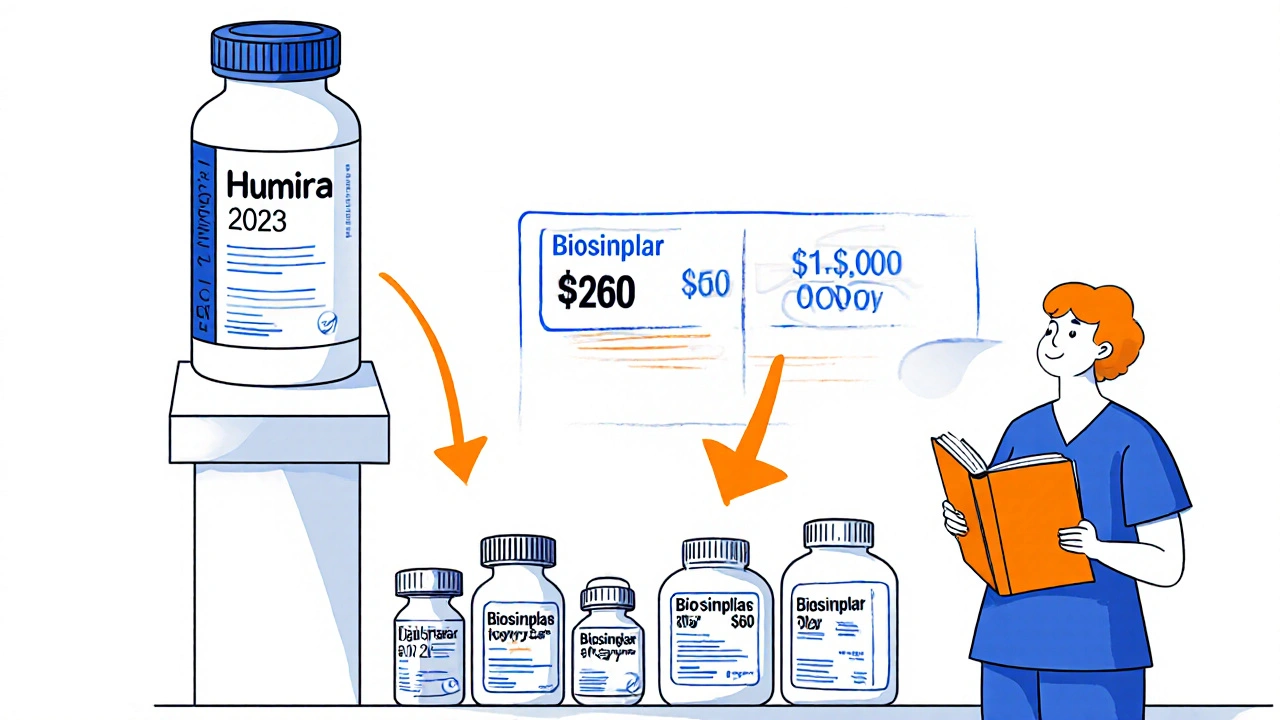

The Patent Cliff: What Happens When the Exclusivity Ends

The moment the last patent or exclusivity expires, it’s called the “patent cliff.” This is when generic manufacturers rush in. And prices drop-fast.

Take Eliquis (apixaban). When its patent expired in December 2022, generic versions captured 35% of the market within six months. By the end of the first year, the average wholesale price dropped 62%. Within 18 months, generics held 90% of the market. That’s the norm for small-molecule drugs.

Biologics are different. These are complex proteins made from living cells, like Humira or Enbrel. Their generic versions are called biosimilars. They’re harder to copy, harder to approve, and harder to swap in. So while generics take over 90% of the market, biosimilars typically reach only 40-60% share after 2 years. That’s why the price drop for biologics is slower-sometimes only 30-40% lower than the brand.

And here’s the irony: even when generics are available, some patients pay more. Insurance companies sometimes put generics on higher tiers to push patients toward the brand. One patient in an FDA public comment said their copay jumped from $50 to $200 after the patent expired-because their insurer didn’t update their formulary in time.

Global Differences: It’s Not Just the U.S.

The U.S. isn’t the only country with patent rules. Japan uses a different system: the maximum patent term is based on the later of five years after filing or three years after requesting examination. That means a drug filed in 2015 might not even get its full 20 years if the patent office takes too long to review it.

Europe has a similar 20-year term but allows for Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), which extend protection for up to 5 years, similar to the U.S. PTE. But the rules are stricter. The EU doesn’t allow pediatric exclusivity extensions unless the company submits data from European children, not just U.S. trials.

India and Brazil have even more aggressive policies. They allow generic manufacturers to produce and export drugs before patent expiration if the drug isn’t being sold locally. This is why you’ll find cheaper versions of U.S. drugs in Africa or Latin America-often years before they’re available at home.

What’s Changing Now? Legislative and Industry Shifts

In 2024, Congress introduced the “Restoring the America Invents Act,” which could eliminate some Patent Term Adjustments. If passed, it could shave 6 to 9 months off the average drug’s exclusivity period. That’s not a huge change-but for companies projecting $60 billion in losses in 2025 alone, every month counts.

The USPTO is also rolling out automated systems to calculate patent term adjustments faster. That means fewer delays on the patent office side-but also fewer chances for companies to game the system with late filings or procedural tricks.

Meanwhile, companies are shifting strategy. Instead of relying on one blockbuster drug, they’re building franchises. AstraZeneca’s Tagrisso (osimertinib) is a great example. The main patent expires in 2026, but they’ve layered on patents for combination therapies, companion diagnostics, and new indications. That pushes the effective exclusivity out to 2033.

Who’s Watching This? And Why It Matters to You

Pharmaceutical companies spend millions on patent strategy teams. Some have 20+ lawyers and regulatory experts just managing one drug’s lifecycle. They track every filing, every extension, every lawsuit. They know exactly when the last patent falls.

For patients, this matters because your access to affordable medicine depends on these timelines. If you’re on a high-cost drug, knowing when its exclusivity ends can help you plan ahead. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask if a generic is coming. Check the FDA’s Orange Book-it’s the official list of approved drugs and their patents. It’s public. You can search it.

For insurers and pharmacies, it’s about cost control. The drop in drug prices after patent expiration saves the U.S. healthcare system tens of billions every year. That’s why generics are pushed so hard after the cliff hits.

And for policymakers, the debate continues: Is 20 years enough? Or is it too long? The WHO says 15 years would balance innovation and access. The pharmaceutical industry says $2.3 billion per drug的研发 cost justifies the current system. The truth? It’s complicated. But one thing’s clear: the 20-year term is just the starting line. The real race is everything that happens after.

How long do drug patents actually last before generics can enter the market?

Most drug patents last 7 to 12 years in practice, even though the legal term is 20 years. This is because the patent clock starts when the application is filed-often 8 to 10 years before the drug is approved by the FDA. Additional protections like regulatory exclusivity and patent term extensions can extend this window, but rarely beyond 14 years from FDA approval.

Can a drug have more than one patent?

Yes. Most drugs are protected by multiple patents covering different aspects: the active ingredient, the chemical formulation, the manufacturing method, how it’s delivered, and how it’s used. These are called a “patent thicket.” The last patent to expire determines when generics can legally enter the market, even if earlier patents have already expired.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect drug patents?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a balance between brand-name and generic drug companies. It allows brand-name companies to extend their patent term by up to 5 years to make up for FDA review delays. At the same time, it lets generic companies file applications before the patent expires, triggering lawsuits that can delay generic entry by up to 30 months. It’s the foundation of how U.S. drug competition works today.

What’s the difference between a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

A patent is a legal right granted by the USPTO to protect an invention. Regulatory exclusivity is a period of market protection granted by the FDA that doesn’t depend on patents. For example, a drug can lose its patent but still be protected by 5 years of New Chemical Entity exclusivity. Generics can’t even apply during that time.

Why do some patients pay more for a drug after its patent expires?

Sometimes, insurance plans don’t update their formularies right away. Even if a generic is available, the insurer may place it on a higher cost tier or require prior authorization. Also, if the drug still has pediatric exclusivity or another regulatory protection, the generic might not be on the market yet-so patients are stuck paying brand prices.

How can I find out when a specific drug’s patent expires?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists all approved drugs and their associated patents and exclusivities. You can search by drug name on the FDA website. It’s free, public, and updated regularly. For biologics, look at the Purple Book. Both are official sources-not third-party sites.

Comments

Ragini Sharma

so like... drug patents are 20 yrs but in reality u get like 7-12? wow. i thought the 20 was the real deal. my insulin is still crazy expensive lmao

Linda Rosie

The discrepancy between legal term and practical exclusivity is a systemic issue.

Vivian C Martinez

This is actually really helpful. I didn’t realize how much of the timeline gets eaten up before the drug even launches. Good breakdown.

Ross Ruprecht

I’m just here waiting for the next pharma CEO to cry about how they need to make back their billion in R&D. Newsflash: they’re not broke.

Bryson Carroll

Patent thickets are just corporate greed dressed up as innovation. The system is rigged and everyone knows it. Why do we still pretend this is fair?

Jennifer Shannon

You know, I’ve been thinking about this for years - the idea that a drug can be invented, tested, approved, and then sold at full price for barely a decade before generics come in... and yet, we still act like 20 years is some kind of fair trade-off. It’s not. It’s a loophole masquerading as law. The FDA’s exclusivities, the Hatch-Waxman Act, the pediatric add-ons - it’s like a Russian nesting doll of delays, each layer designed to keep prices high. And then you have patients who can’t afford the brand, can’t get the generic because of insurance tiers, and wonder why healthcare is broken. It’s not the system failing - it’s working exactly as intended for the people who designed it.

Suzan Wanjiru

Orange Book is your best friend if you’re on a long term med. Check it every 6 months. You’d be shocked how often generics pop up before you expect

Kezia Katherine Lewis

The regulatory exclusivity framework operates as a non-patent barrier to entry, effectively extending market exclusivity through administrative mechanisms rather than intellectual property rights. This creates a dual-layered protection regime that significantly impedes biosimilar and generic market penetration.

Henrik Stacke

I find it fascinating how the U.S. system diverges so sharply from Europe’s SPCs and India’s compulsory licensing. It’s not just about law - it’s about cultural attitudes toward innovation, access, and corporate power. In the UK, we’re more likely to question whether a $100,000-a-year drug is worth it - here, we just shrug and pay.

Manjistha Roy

I remember when my brother needed a rare disease drug that had orphan exclusivity - even though the patent had expired, no generic could enter for seven years. He had to travel to Canada just to get it at half the price. This isn’t about innovation anymore - it’s about control.

Jennifer Skolney

This is why I always tell my friends to check the FDA’s Purple Book for biologics - it’s not as well known but it’s just as important. And yes, biosimilars are slower to catch on, but they’re coming. 💪

JD Mette

I never realized how much of this is about timing and paperwork. Miss a 60-day window and you lose years of revenue. That’s wild.

Olanrewaju Jeph

In Nigeria, we get cheaper versions of these drugs years before the U.S. because of parallel imports. It’s not ideal, but it’s what keeps people alive. The system here is broken, but at least we know where to look.

Dalton Adams

You’re all missing the point. The real issue isn’t the patent term - it’s that the FDA approval process is a bureaucratic nightmare. If they’d just speed up reviews, we wouldn’t need all these extensions. Also, biosimilars are inferior. Why should I take a cheaper version that’s not *exactly* the same? 😒

Demi-Louise Brown

I work in pharmacy and see this every day. Patients are confused when their insulin price doesn’t drop after the patent expires. They don’t know about regulatory exclusivity or formulary delays. We need better public education - not just for patients, but for providers too.