When people talk about COPD, they often treat it like one disease. But that’s not accurate. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are two distinct problems that both fall under the COPD umbrella - and treating them the same way can make things worse. If you or someone you care about has been diagnosed with COPD, understanding which component is dominant isn’t just academic. It affects how you breathe, what treatments work, and even how long you can stay active.

What Exactly Is Going on in Your Lungs?

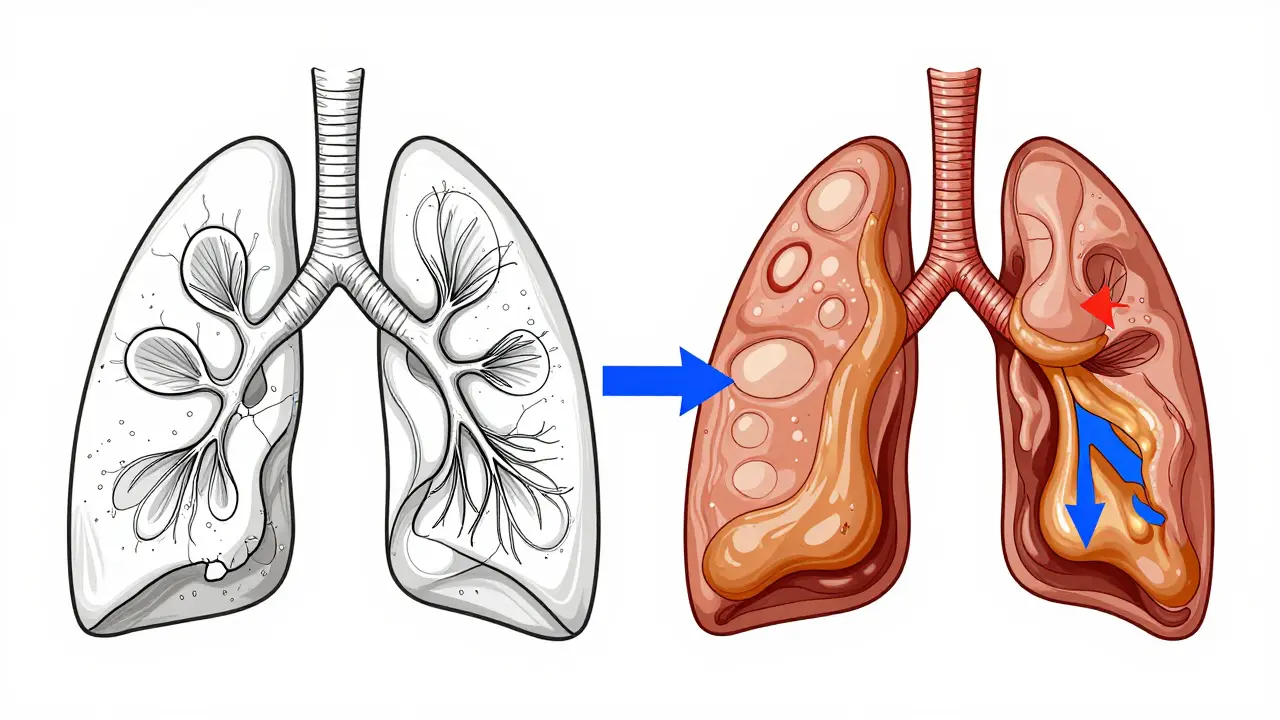

Imagine your lungs as a network of tiny air sacs - alveoli - surrounded by elastic fibers that help them expand and deflate. In emphysema, those fibers break down. The walls between the air sacs collapse, creating large, inefficient spaces instead of many small ones. This isn’t just inflammation - it’s permanent structural damage. You lose up to 50% of your lung’s natural recoil. That means air gets trapped, oxygen can’t get in efficiently, and carbon dioxide builds up. By the time symptoms show up, you’ve already lost a significant chunk of lung function.

Chronic bronchitis is different. It’s not about broken air sacs - it’s about clogged airways. The lining of your bronchial tubes swells, and your body produces way too much mucus. Goblet cells, which normally make a little mucus to trap dust and germs, multiply by 300-500%. Instead of 10-100 mL of mucus a day, you’re producing 100-200 mL. That’s like a pint of thick phlegm every 24 hours. The tiny hair-like cilia that sweep mucus out get paralyzed, so it piles up. You’re not just coughing - you’re fighting to clear your airways.

Symptoms: Cough vs. Shortness of Breath

If you’re wondering which condition you might be dealing with, start with symptoms. Chronic bronchitis usually starts with a persistent, wet cough - the kind that lingers for months, comes back every winter, and produces noticeable mucus. Many people describe it as having a "rattle" in their chest. You might need to clear your throat constantly. In fact, the clinical definition is simple: a productive cough for at least three months in two years straight.

Emphysema doesn’t start with coughing. It starts with breathlessness. At first, it’s just when you walk uphill or carry groceries. Then it’s walking across the room. Eventually, even sitting still feels like a workout. People with emphysema often describe it as "air hunger" - like you’re trying to suck air through a straw. They speak in short phrases because taking a full breath takes too much effort. One patient on a COPD forum said, "I can only say five words before I need to stop and breathe." That’s not exaggeration - it’s a direct result of losing lung surface area for gas exchange.

The "Pink Puffer" and "Blue Bloater" - Real Phenotypes, Not Just Myths

You’ve probably heard these terms. They’re outdated in some circles, but they still describe real patterns seen in clinics. The "pink puffer" is the emphysema patient. They’re often thin, breathe fast (25-30 breaths per minute), and have a barrel chest from overinflated lungs. Their skin stays pink because they’re hyperventilating to keep oxygen levels up - even if they’re barely breathing. Oxygen saturation is usually 92-95%.

The "blue bloater" is the chronic bronchitis patient. Their skin may look bluish, especially around the lips or fingertips, because their blood oxygen is low (85-89%). They retain fluid - swollen ankles, a distended belly - because their heart is straining from low oxygen. This is called cor pulmonale: right-sided heart failure caused by lung disease. They’re often heavier, and their cough is constant. The term "bloater" comes from the fluid buildup and the fact that their lungs are filled with mucus, not air.

But here’s the catch: 85% of people with advanced COPD have features of both. You’re not just one or the other. But one side usually dominates - and that’s what guides treatment.

How Doctors Tell Them Apart

A simple spirometry test (breathing into a tube) shows airflow obstruction in both. But that’s not enough. The real clues come from more specific tests.

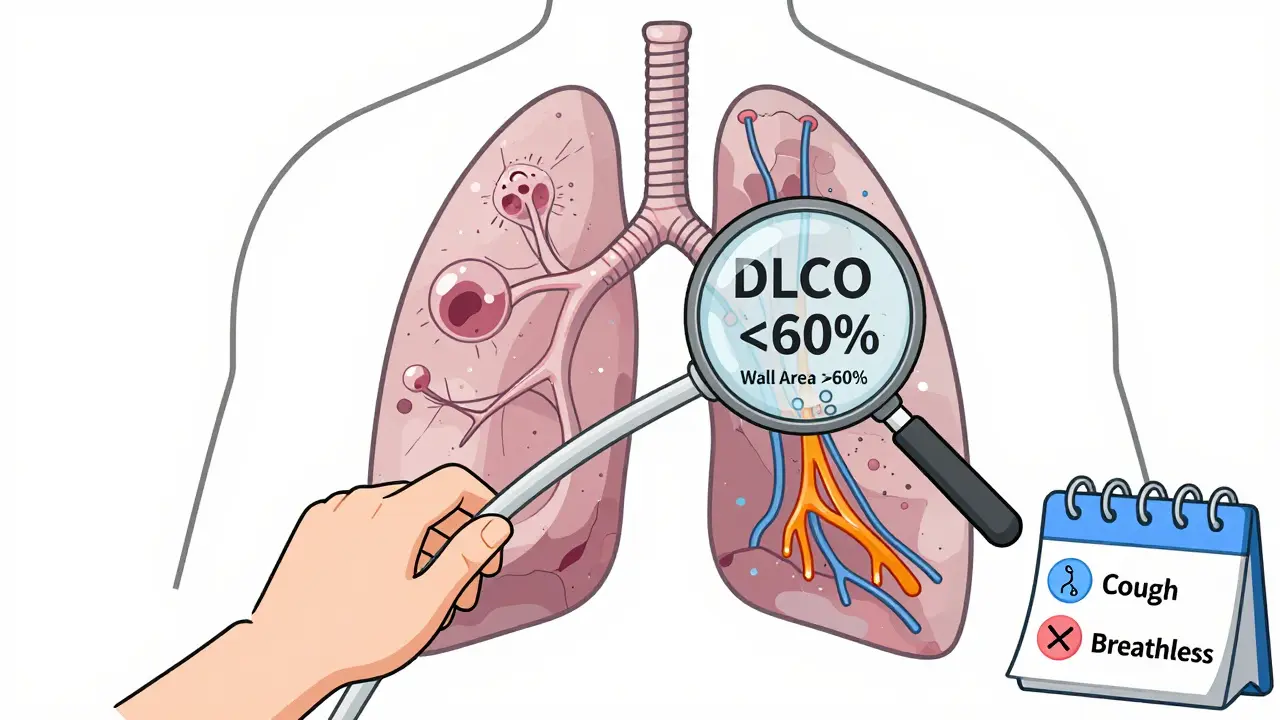

- DLCO (diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide): If this is below 60% of predicted, emphysema is likely. It measures how well oxygen moves from your lungs into your blood - and emphysema ruins that.

- 6-minute walk test: Emphysema patients drop their oxygen saturation below 88% within two minutes. Chronic bronchitis patients usually stay above 90% but stop because they’re too out of breath.

- CT scan: Emphysema shows up as dark, low-density patches covering more than 15% of the lung. Chronic bronchitis shows thickened airway walls - wall area percentage over 60% on expiratory scans.

Many doctors skip these tests because they’re not routine. But if you’re not getting them, you’re being treated blindly.

Treatment Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All

Here’s where it gets critical. Using the wrong treatment can do more harm than good.

For chronic bronchitis, reducing mucus is key. Mucolytics like carbocisteine cut exacerbations by 22%. Nebulized hypertonic saline - a saltwater mist - thins mucus and helps clear it. One study showed 73% of patients felt less stuck. Roflumilast, a pill that reduces airway inflammation, lowers flare-ups by 17.3% in people with frequent exacerbations. But if you have emphysema, these won’t help much.

Emphysema needs different tools. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction - using tiny valves to collapse damaged lung areas - improves walking distance by 35% in eligible patients. Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) helps those with upper-lobe disease and very low FEV1. And if you have alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (1-2% of emphysema cases), weekly infusions of the missing protein can slow decline.

But here’s the danger: Inhaled steroids. They’re common in COPD, but they increase pneumonia risk by 40% in chronic bronchitis patients. That’s why guidelines now recommend LAMA/LABA combos (long-acting bronchodilators) as first-line for bronchitis-dominant cases. Emphysema patients benefit more from long-acting bronchodilators too, but they’re better candidates for advanced interventions.

Quality of Life: What Daily Life Looks Like

On patient forums, the differences are stark. Chronic bronchitis patients spend hours on chest physiotherapy - tapping their chest, using vibrating devices, or even lying in weird positions to drain mucus. One Reddit user measured 100 mL of mucus every morning for eight years. That’s not a metaphor. That’s their reality.

Emphysema patients talk about mobility. They hate oxygen tanks because they’re heavy. Portable concentrators help, but they’re still a tether. One man said, "I used to hike. Now I can’t walk to the mailbox without stopping." Their biggest fear isn’t coughing - it’s running out of air while talking to their grandkids.

Both groups struggle with medication routines. Six in ten chronic bronchitis patients can’t keep up with four or five daily inhalers. Half of emphysema patients say oxygen therapy makes them feel trapped. It’s not laziness - it’s the physical and mental toll of managing a disease that steals your breath.

The Future Is Personalized

The field is shifting. In 2023, the FDA approved inhaled alpha-1 antitrypsin for genetic emphysema - a treatment that improved lung function by 20% in a year. In 2024, Europe launched a new acoustic device that vibrates mucus loose for chronic bronchitis patients - cutting flare-ups by 32%.

Research is now looking at blood biomarkers. If your eosinophil count is over 300 cells/μL, you might respond to biologics designed for bronchitis. The NIH is tracking 10,000 patients through 2026 to find these patterns.

What this means: COPD isn’t one disease. It’s a spectrum. And if your doctor doesn’t ask about your cough, your breathing pattern, your mucus volume, or your oxygen levels - you need to ask for better.

What You Should Do Now

If you have COPD:

- Ask for a DLCO test. If it’s below 60%, emphysema is likely.

- Track your symptoms: Is it mostly cough and mucus? Or shortness of breath with little cough?

- Review your meds. Are you on steroids? If you have a lot of mucus, you might be at higher risk for pneumonia.

- Find out if you’re eligible for lung volume reduction - especially if you’re thin, have hyperinflation, and your FEV1 is below 35%.

- Join a support group. The COPD Foundation has local chapters and forums where people share real strategies - not just textbook advice.

The goal isn’t just to manage symptoms. It’s to keep you moving, breathing, and living - and that starts with knowing which part of your lungs is failing.

Can chronic bronchitis turn into emphysema?

No, chronic bronchitis doesn’t turn into emphysema. They’re separate processes caused by the same thing - usually smoking or long-term air pollution. But they often occur together. Someone can have both, and one may become more dominant over time. What changes isn’t the disease type - it’s the balance of damage in your lungs.

Is COPD reversible?

No, the structural damage from emphysema and the chronic inflammation in bronchitis aren’t reversible. But you can stop it from getting worse. Quitting smoking is the single most effective step - it cuts decline in half. Medications, oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehab, and lifestyle changes can significantly improve quality of life and slow progression.

Why do some COPD patients need oxygen and others don’t?

It depends on how much lung damage you have and how well your blood carries oxygen. Emphysema patients often need oxygen because their lungs can’t transfer enough oxygen into the blood. Chronic bronchitis patients may not need oxygen until later - their issue is mucus blocking airflow, not poor gas exchange. But if their oxygen drops below 88% at rest or during activity, oxygen therapy becomes necessary to protect the heart and brain.

Are inhalers enough to treat COPD?

Inhalers help, but they’re not enough on their own. Bronchodilators open airways, but they don’t fix mucus buildup or destroyed alveoli. For chronic bronchitis, you may need mucolytics or airway clearance techniques. For emphysema, advanced options like lung volume reduction or even surgery may be needed. Pulmonary rehab - exercise, education, breathing training - is just as important as any inhaler.

What’s the biggest mistake people make with COPD?

Assuming all COPD is the same. Taking steroids when you have chronic bronchitis increases pneumonia risk. Not testing for DLCO means missing emphysema. Ignoring mucus clearance leads to repeated infections. And quitting smoking too late - after severe damage is done - means losing the best chance to slow decline. Knowledge is power, and the right treatment starts with the right diagnosis.

Comments

Simon Critchley

Man, this post is a masterclass in COPD breakdowns. Let’s get real - chronic bronchitis isn’t just ‘coughing up phlegm,’ it’s your lungs drowning in a swamp of goblet cell overdrive. 300-500% increase?! That’s not a medical condition, that’s a biological mutiny. And the mucus volume? A pint a day? I’ve seen guys with nebulizers looking like they’re brewing tea in their chest. We need more of this level of detail - not just ‘COPD = bad lungs’ but ‘here’s exactly which part of your lung is staging a coup.’

DLCO under 60%? That’s the smoking gun. If your doc doesn’t order it, fire ‘em. I had a buddy who got misdiagnosed for 4 years as ‘just a smoker’s cough’ - turned out his DLCO was 38%. He was walking around with 40% of his gas exchange capacity gone. Dude’s now on home oxygen and still hikes on weekends. Because he got the *right* treatment. Knowledge is power, but actionable data? That’s the real MVP.

Also, pink puffer vs. blue bloater? Still 100% valid. I work in pulmonology. Saw a blue bloater last week - BP 180/95, SpO2 87%, ankles like overinflated balloons. He was on steroids. I almost cried. Steroids in mucus-dominant COPD? It’s like pouring gasoline on a grease fire. LAMA/LABA first. Always. And if you’re not doing airway clearance? You’re not treating. You’re just waiting.

Karianne Jackson

I hate this disease.

Tom Forwood

Yo this is wild. I’ve got my pops on LAMA/LABA after his DLCO came back trash - 41%. He used to be a mechanic, now he can’t lift a wrench without huffing like he just ran a marathon. But man, since we started the hypertonic saline nebulizer? He’s coughing less and actually sleeping through the night. No more 3am ‘I can’t breathe’ panic. Also, he’s not on steroids anymore. Doc said ‘if you’re coughing up enough to fill a coffee mug daily, steroids are not your friend.’

Also, the ‘pink puffer’ thing? My uncle was one. Thin as a rail, always hyperventilating, never coughed. We thought he was just ‘nervous’ until his CT showed 22% emphysema. Dude looked like a deflated balloon with legs. Scary stuff.

Biggest win? Pulmonary rehab. He didn’t believe in it till he did. Now he does leg lifts with soup cans and calls it ‘tough love for his lungs.’

John McDonald

This is exactly why we need to stop treating COPD like a monolith. I’m a respiratory therapist, and I see this every day. Patients get handed an inhaler like it’s a magic wand. But if you’ve got bronchitis-dominant COPD and you’re not doing airway clearance, you’re just setting yourself up for a cycle of infections and ER visits.

One patient I had - 68, lifelong smoker, 100 mL mucus every morning - started using the Flutter device daily. After 3 weeks, his exacerbations dropped from monthly to once every 4 months. That’s not luck. That’s targeted care. And guess what? He didn’t need steroids. He needed technique.

And for emphysema? Bronchoscopic volume reduction isn’t sci-fi anymore. It’s covered by Medicare for the right candidates. If you’re thin, have upper-lobe destruction, and FEV1 under 35%? You’re a candidate. Talk to your pulmonologist. Don’t wait until you’re on 4L oxygen just to sit on the couch.

We can do better. We just have to stop pretending one size fits all.

Chelsea Cook

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me the ‘blue bloater’ is basically a human swamp with legs? And we’re still giving them steroids like it’s a spa day? 😂

I had my aunt on prednisone for 2 years because ‘it helps inflammation.’ Turns out she got pneumonia 3 times. She’s now on hypertonic saline, a vibrating vest, and a new lease on life. Also, she stopped smoking. Shocking, I know.

But here’s the kicker: she said the worst part wasn’t the cough or the oxygen tank. It was the shame. People think if you’re wheezing, you’re ‘just a smoker.’ Like it’s a moral failure. Nah. It’s biology. And we need to stop making patients feel guilty while we’re still treating them like they’re in a 1990s medical textbook.

Andy Cortez

THIS IS ALL JUST A BIG PHARMA SCAM. I read a blog that said COPD is caused by 5G and the government’s secret fluoride agenda. You think they’re giving you LAMA/LABA? Nah. They’re just keeping you hooked on inhalers so Big Pharma can keep raking in billions. DLCO? That’s just a fancy word for ‘pay $800 for a test so they can upsell you oxygen.’

I quit smoking 15 years ago. My lungs are fine. I just breathe deep and drink apple cider vinegar. Works better than any ‘science’ they push. Also, your doctor is lying to you. They get commissions on inhalers. Ask them. They’ll look away.

Jacob den Hollander

I just want to say… thank you. This post didn’t just explain things - it gave me hope. My dad’s got both, but bronchitis-dominant. He was told ‘just use your inhaler’ for years. Then he found a pulmonary rehab center. Now he does breathing exercises, chest physio, and even joins a weekly support group. He says he feels like he’s getting his life back - not just managing symptoms.

I used to think COPD was just ‘getting old and out of breath.’ Now I see it as a complex, personal battle. And honestly? It’s made me a better caregiver. I don’t just ask ‘how are you?’ anymore. I ask ‘did you clear your chest today?’

To anyone reading this: if you or someone you love has COPD, don’t accept ‘it’s just COPD’ as an answer. Push for DLCO. Push for airway clearance. Push for a plan that fits *them*. You’re not being difficult. You’re being a lifeline.

Andrew Jackson

It is a profound and lamentable tragedy that the modern medical establishment has reduced the noble and ancient struggle of human pulmonary function to a series of algorithmic, pharmaceutical interventions. The human lung, a divine instrument of respiration, has been commodified into a malfunctioning machine to be patched with LAMA/LABA, nebulizers, and invasive bronchoscopic valves - all orchestrated by profit-driven conglomerates who have abandoned the Hippocratic Oath in favor of shareholder dividends.

Our ancestors breathed clean air, walked daily, and died with dignity. Now, we are medicated, monitored, and mechanized into submission. The notion that one may ‘slow decline’ is a cruel illusion. Decline is inevitable. The only virtue lies in accepting it with stoicism - not in chasing false hope through diagnostic tests and experimental devices.

Let us not forget: the body is not a machine to be fixed. It is a temple. And we, as a society, have turned it into a service contract.

Joseph Charles Colin

Just to clarify some nuances: the 2024 European acoustic device - the VibraClear - isn’t just vibrating mucus. It’s using low-frequency acoustic resonance to disrupt mucus viscoelasticity at 80 Hz, which is the sweet spot for breaking up mucin polymer networks. That’s why it cuts exacerbations by 32%. Most devices are just mechanical shakers - this one’s tuned to the biochemistry.

Also, eosinophil count over 300? That’s not just a biomarker - it’s a predictor of IL-5 pathway activation. Biologics like mepolizumab (anti-IL5) are now being trialed for non-asthmatic, eosinophilic bronchitis. Phase 2 data shows 41% reduction in exacerbations. This isn’t ‘off-label’ - it’s next-gen phenotyping.

And for those asking about alpha-1 antitrypsin: the new inhaled version (AAT-HI) delivers 10x the lung concentration of IV infusion, with 80% lower systemic exposure. No more weekly IVs. Just a puff twice daily. FDA approved in 2023. If you’ve got the deficiency, this is game-changing.

Bottom line: COPD is evolving. We’re moving from ‘one size fits all’ to precision phenotyping. The tools are here. The question is - are we using them?

John Sonnenberg

My dad had COPD for 12 years… and he died last year… because he didn’t get the right care… he was told to ‘just use the inhaler’… he didn’t know about DLCO… he didn’t know about mucus clearance… he didn’t know he was a blue bloater… he just… kept breathing… until he couldn’t…

Don’t let this happen to someone you love…

Ask for the test…

Ask for the right treatment…

Don’t wait…

Joshua Smith

This is the most helpful thing I’ve read on COPD in years. I’ve been helping my mom manage her diagnosis, and I had no idea how different bronchitis and emphysema were. I thought it was all just ‘bad lungs.’ Now I get why she coughs all day but doesn’t get short of breath until she climbs stairs - classic bronchitis-dominant.

We just started her on carbocisteine and a vibrating chest vest. She says it’s ‘weird but works.’ I’m going to ask her pulmonologist for a DLCO next visit. And I’m definitely not letting her stay on steroids.

Also, I had no idea pulmonary rehab existed. We’re signing her up. I feel like I finally have a plan, not just panic.

Thanks for writing this. Seriously. It’s rare to find something this clear and practical.