Hypoglycemia Risk Calculator

This tool assesses your risk of hypoglycemia unawareness when taking insulin and beta-blockers. Based on your medication choice and monitoring habits, it provides personalized safety recommendations.

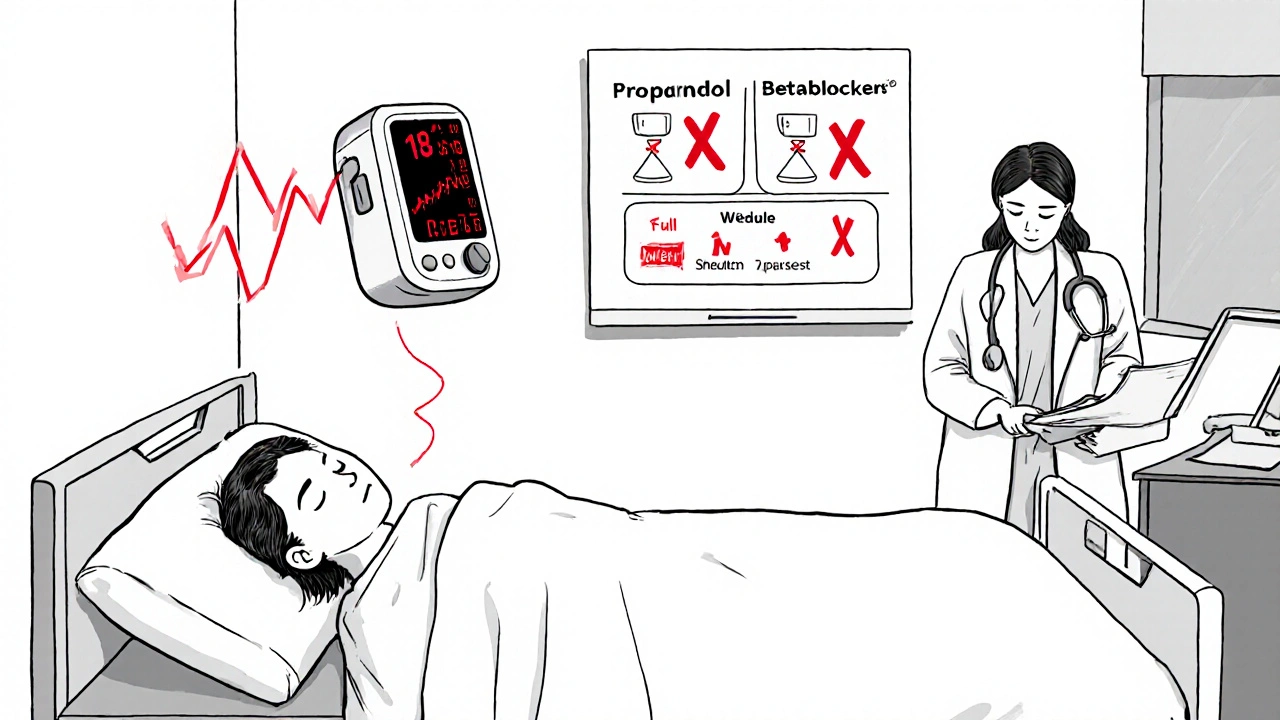

Critical Safety Instructions

Why Insulin and Beta-Blockers Together Can Be Dangerous

If you're taking insulin for diabetes and also prescribed a beta-blocker for high blood pressure or heart disease, you're at higher risk for a silent, life-threatening danger: hypoglycemia unawareness. This isn't just a minor side effect-it's a condition where your body stops sending you the usual warning signs that your blood sugar is dropping. And because beta-blockers block those signals, you could pass out before you even realize something’s wrong.

How Hypoglycemia Unawareness Works

When your blood sugar drops too low, your body normally triggers a fight-or-flight response. You might feel shaky, your heart races, you start sweating, or you get anxious. These are your body’s alarms. But in people with diabetes-especially those with type 1-repeated low blood sugar episodes can dull these signals over time. That’s hypoglycemia unawareness. Now, add a beta-blocker into the mix, and it gets worse.

Beta-blockers like metoprolol or atenolol block adrenaline. That’s good for your heart-it lowers your pulse and blood pressure. But it also shuts down the physical signs of low blood sugar: tremors, fast heartbeat, and nervousness. You lose the early warning system. And here’s the catch: you still sweat. That’s because sweating is controlled by a different pathway (acetylcholine, not adrenaline). So if you’re on a beta-blocker, sweating might be the only clue left that your blood sugar is crashing.

The Real Risk: Not Just Masked Symptoms, But Slowed Recovery

It’s not just that beta-blockers hide the symptoms-they also make it harder for your body to fix low blood sugar. Your liver normally releases stored glucose when your levels drop. Beta-blockers, especially the selective ones, block the beta-2 receptors that tell your liver to release that glucose. That means even if you notice you’re low, your body can’t correct it fast enough. This double whammy-no warning signs + no recovery-is why hospital stays become so dangerous.

Studies show that 68% of hypoglycemia events in diabetic patients on beta-blockers happen within the first 24 hours of hospital admission. That’s when insulin doses are being adjusted, meals are irregular, and stress levels are high. One 2019 study found patients on selective beta-blockers had 2.3 times higher odds of hypoglycemia than those not on them. And the death risk? Patients on these drugs had a 28% higher chance of dying from a low blood sugar episode.

Not All Beta-Blockers Are the Same

Here’s where things get practical: not every beta-blocker carries the same risk. The old-school, non-selective ones like propranolol are the worst offenders-they block all beta receptors, including those in the liver and muscles. That means they wipe out almost all warning signs and severely limit glucose recovery.

Cardioselective beta-blockers like metoprolol or atenolol are better, but still risky. They mainly target the heart, but they still interfere with liver glucose release. Then there’s carvedilol. It’s different. It’s not just a beta-blocker-it also blocks alpha receptors, which may help preserve some glucose counter-regulation. Research shows carvedilol is linked to significantly lower rates of severe hypoglycemia compared to metoprolol. In fact, one 2022 guideline noted a 17% drop in severe low blood sugar events when patients switched from metoprolol to carvedilol.

That’s why many endocrinologists and cardiologists now recommend carvedilol as the first-choice beta-blocker for diabetic patients who need one. It’s not perfect, but it’s the safest option we have.

What Hospitals Do to Protect You

Hospitals know this is a ticking time bomb. The American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association both recommend strict monitoring for diabetic patients on beta-blockers. That means checking your blood sugar every 2 to 4 hours-no exceptions. If you’re on insulin, they’ll often use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) instead of fingersticks. These devices beep when your sugar dips, even if you don’t feel it.

Since 2018, CGM use in diabetic patients on beta-blockers has jumped 300%. And the results? A 42% drop in severe hypoglycemia events. That’s not a small win. It’s life-saving.

What You Can Do as a Patient

If you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker, here’s what you need to do right now:

- Know your warning signs. Sweating is your main clue. If you break out in a cold sweat for no reason, check your blood sugar-even if you feel fine.

- Check your blood sugar more often. Don’t wait for symptoms. Check before meals, before bed, and if you feel “off.”

- Ask your doctor about carvedilol. If you’re on metoprolol or atenolol, ask if switching could reduce your risk.

- Get a CGM. If you’ve had a low blood sugar episode before, or if you’re unaware of lows, a CGM is not optional-it’s essential.

- Carry fast-acting sugar. Glucose tablets, juice, or candy. Keep them everywhere-your car, your purse, your bedside.

- Tell people around you. Your family, coworkers, friends. Teach them to recognize sweating as a sign of low blood sugar and to help you if you’re confused or unresponsive.

What About Long-Term Risk?

You might hear that big studies like the ADVANCE trial found no major difference in hypoglycemia rates over five years between patients on beta-blockers and those on placebo. That’s true-but those were outpatient studies with stable insulin regimens. The danger spikes in hospitals, during illness, or when doses change. That’s where most of the harm happens.

Also, don’t stop your beta-blocker because you’re scared. For people who’ve had a heart attack, beta-blockers cut the risk of dying from heart problems by 25%. That’s huge. The goal isn’t to avoid them-it’s to use them safely.

The Future: Personalized Medicine

Researchers are now looking at genetics to predict who’s most at risk. The 2023 DIAMOND trial is testing whether certain gene variants make some people more likely to develop hypoglycemia unawareness when on beta-blockers. In the future, your doctor might run a simple blood test before prescribing one-and choose a safer option based on your DNA.

Until then, the best strategy is simple: know your risks, monitor closely, use the safest beta-blocker possible, and never ignore sweating as a warning.

Bottom Line

Insulin and beta-blockers can be a dangerous combo-but it’s not a death sentence. With awareness, better drug choices, and smart monitoring, you can manage both your heart and your blood sugar safely. The key is not avoiding treatment, but using it wisely. Your body still has one alarm left: sweating. Learn to listen to it.

Comments

peter richardson

I've been on metoprolol for 8 years and insulin for 12. Never had an issue. Maybe it's just me but I think people blow this out of proportion. I check my sugars like clockwork and I'm fine.

Uttam Patel

Sweating is your only warning? Cool. So next time I break out in a cold sweat at my desk I should assume it's not the AC breaking but my blood sugar crashing? Thanks for the life advice.

Kirk Elifson

They're pushing carvedilol because Big Pharma owns the guidelines now. You think this is science? Nah. It's profit. They want you on the expensive one so they can upsell CGMs and 'specialized' insulin pens. Wake up.

Nolan Kiser

This is actually one of the most accurate summaries I've seen. The liver's glucose release being blocked by beta-2 antagonism is the real silent killer. Most docs don't even know this. Carvedilol's alpha-blockade helps preserve some counter-regulation - it's not magic, but it's the best we've got. CGMs aren't optional for anyone on this combo. Period.

Yaseen Muhammad

The distinction between non-selective and cardioselective beta-blockers is critical, and the data supporting carvedilol's relative safety in diabetic patients is robust. However, individual variability in drug metabolism and receptor sensitivity means that even 'safer' options require personalized titration and monitoring. Do not assume safety based on class alone.

Dylan Kane

Wow. So now I’m supposed to carry juice everywhere and beg my coworkers to monitor me like I’m a toddler? Thanks for making me feel like a medical liability.

KC Liu

The 2019 study? That was funded by Abbott. The 2022 guideline? Written by endocrinologists who get kickbacks from CGM companies. And the 300% jump in CGM use? That’s because hospitals are now billing $1200 per day for monitoring. This isn’t medicine - it’s a revenue stream disguised as safety.

Sam Tyler

I've been a diabetic for 22 years and on beta-blockers since my heart attack in 2015. I switched from metoprolol to carvedilol last year after a scary episode where I passed out in the grocery store and didn't know why. The difference? Night and day. I still sweat when I'm low - that's my signal now. I got a CGM, and it's the best thing I've ever done for myself. You don't have to live in fear. You just have to be smart. And yes, it's a lot of work. But your life? Worth it.

shridhar shanbhag

I'm from India, and here most people can't even afford insulin, let alone CGMs. Carvedilol? We don't even have it in rural clinics. So while this is great info for folks in the US, for the rest of us? We just pray and check sugars with our fingers every few hours. No fancy tech. Just survival.

John Dumproff

This hit hard. I used to ignore sweating because I thought it was just stress. Then I had a seizure in my sleep. My wife found me at 3am. I didn't know anything had happened until I woke up in the ER. I didn't feel a thing. That's when I started checking every 2 hours. I'm not scared anymore - I'm just careful. And I carry glucose tabs in my sock now. Weird? Maybe. Safe? Absolutely.

Lugene Blair

You're not broken because you need extra tools. You're just smart. Carrying glucose? Checkin' your sugar? Asking your doc about carvedilol? That’s not being paranoid - that’s being in control. You’ve got this. And if you're reading this? You're already ahead of 90% of people who don’t even know this is a thing.

Ellen Frida

I think this whole thing is about control - society wants us to monitor everything, to be afraid of our own bodies, to trust machines more than instincts. Maybe we’re supposed to feel low... maybe it's a message. Maybe the body knows better than the lab results.

Michael Harris

You say sweating is the only sign? That’s a joke. I’ve been sweating since I was 12 and it’s just because I’m fat. You want me to start popping glucose tablets every time I get hot? This is medical gaslighting disguised as advice.

Cosmas Opurum

This is what happens when Western medicine tries to fix everything with pills and gadgets. In Nigeria, we use ginger, bitter leaf, and prayer. No CGM. No carvedilol. Just faith and tradition. You think your expensive monitor saves you? We’ve been living with diabetes for centuries without it. Maybe the problem isn’t the body - it’s the system that tells you you’re broken.