Generic drugs save patients and the healthcare system billions each year. In the U.S., 90.7% of all prescriptions filled are for generics-yet they make up just 23% of total drug spending. That’s a massive win for affordability. But behind those numbers is a quiet, critical job pharmacists do every day: spotting when a generic isn’t working like it should.

Most generics are perfectly safe and effective. The FDA requires them to match brand-name drugs in active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They must also prove bioequivalence-meaning the body absorbs the drug within 80% to 125% of the brand’s rate. That’s a wide window. For most medications, it doesn’t matter. But for some, it absolutely does.

When a 20% Difference Isn’t Just a Number

Think of a generic drug like a copy of a key. If it’s slightly off, your door might still open. But if you’re trying to unlock a high-security safe, even a tiny misalignment can lock you out. That’s what happens with narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. These are medications where the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is razor-thin.

Drugs like levothyroxine (for thyroid), warfarin (a blood thinner), phenytoin (for seizures), and digoxin (for heart rhythm) fall into this category. A 2021 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that switching between different generic versions of NTI drugs led to 2.3 times more therapeutic failures than with non-NTI drugs. One patient might be stable on a brand-name version, then switch to a generic-and within weeks, their TSH levels spike from 2.1 to 8.7. That’s not a fluke. That’s a clinical emergency.

Pharmacists need to know: if a patient reports sudden changes in symptoms after a generic switch-especially with NTI drugs-it’s not just "maybe it’s stress." It’s a red flag. And it’s the pharmacist’s job to investigate.

Look-Alike, Sound-Alike: The Silent Killer

It’s not always about chemistry. Sometimes, it’s about confusion.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices reports that 14.3% of all generic medication errors come from look-alike or sound-alike names. Think oxycodone/acetaminophen vs. hydrocodone/acetaminophen. One letter. One syllable. But one can cause respiratory depression; the other, less so. Or clonazepam vs. clonidine. One treats seizures, the other high blood pressure. Mix them up, and you’ve got a disaster.

Pharmacists see this every day. A patient walks in with a prescription for hydrocodone. The pharmacy’s system auto-fills the generic. But the bottle says “oxycodone.” The label looks right. The pill color matches. The patient takes it. And then they’re too drowsy to drive home.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2022, a survey of 1,247 pharmacists found that 63.2% had encountered at least one problematic generic substitution in the past year. Nearly 29% reported actual patient harm.

That’s why pharmacists must pause. Always check the manufacturer. Always confirm the pill imprint. Always ask: “Has this been switched recently?”

Extended-Release Formulations: The Hidden Trap

Not all generics are created equal-even if they have the same active ingredient.

Extended-release (ER) pills, patches, and capsules are designed to release medication slowly over hours. That’s tricky to replicate. The coating, the matrix, the particle size-all matter. And not every manufacturer gets it right.

In 2020, FDA testing found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution testing. That means the drug didn’t release as expected. Some patients got too much too fast. Others got too little. Both are dangerous.

The FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication in 2023 about specific generic versions of diltiazem CD, a heart medication. Between January 2021 and March 2022, there were 47 reported cases of therapeutic failure-patients experiencing chest pain or irregular heartbeat after switching manufacturers. The problem? Inconsistent drug release profiles.

Pharmacists can’t assume all ER generics are equal. If a patient on a generic ER version of diltiazem, metoprolol, or methylphenidate starts having breakthrough symptoms, the pharmacist must trace the manufacturer. A change in pill shape, color, or even the imprint code can be a clue.

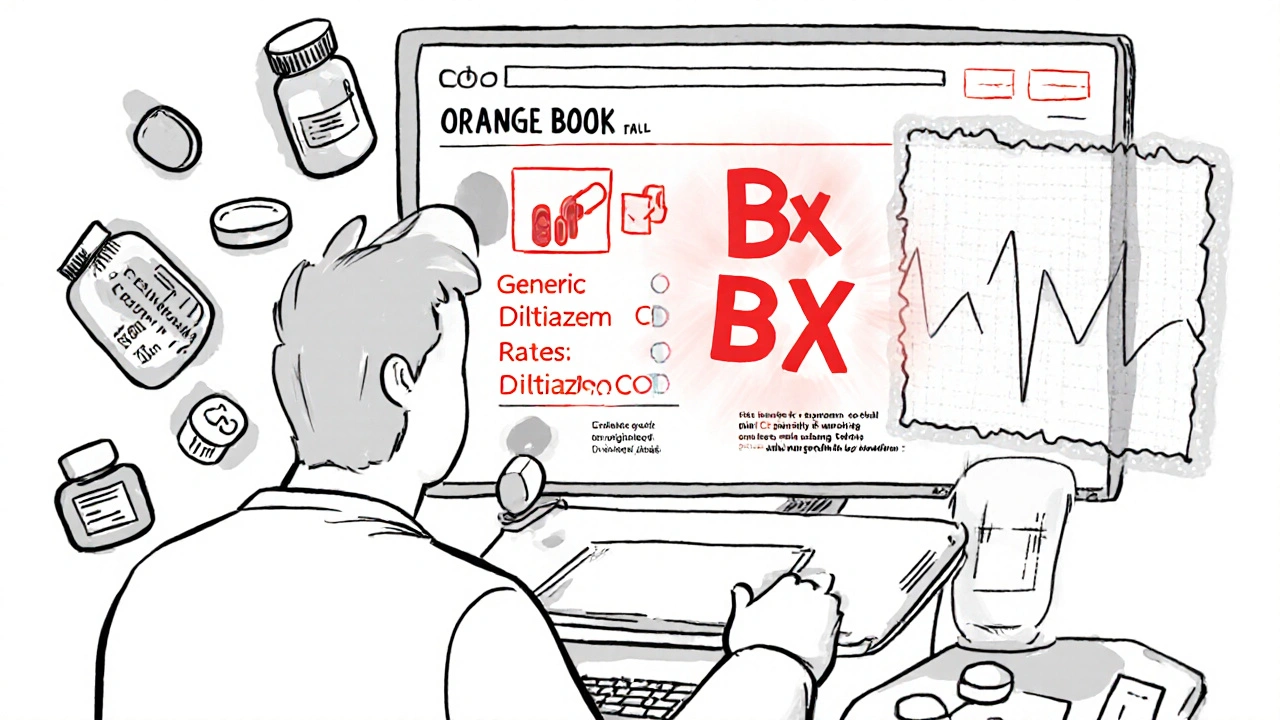

The Orange Book Isn’t Just a Book-It’s Your Lifeline

The FDA’s Orange Book (officially the “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations”) is the single most important tool a pharmacist has when evaluating generics.

Every drug in the Orange Book has a therapeutic equivalence code:

- AB = Therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. Safe to substitute.

- BX = Not therapeutically equivalent. Don’t substitute without consulting the prescriber.

As of October 2023, over 10% of generic drugs in the Orange Book carry a BX rating. That’s not a typo. That’s 1,500+ products flagged as potentially problematic.

Pharmacists must check the Orange Book before dispensing-especially for NTI drugs. If a generic is BX-rated, you can’t just fill it and assume it’s fine. You need to call the prescriber. You need to explain the risk. And you need to document it.

Some states, like New York and Massachusetts, have laws requiring pharmacists to notify prescribers before substituting NTI generics. But even in states without those rules, it’s professional responsibility.

What Patients Tell You Matters More Than You Think

Patients don’t always know what’s wrong. But they know how they feel.

A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found that while 78.3% of patients were happy with generics because of cost, 22.4% reported different side effects after switching manufacturers. That’s over one in five. And 37.6% of patient complaints to the FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development program were about inconsistent effectiveness.

One patient says: “I’ve been on this generic for years, but last month I switched and now I’m nauseous all day.” Another: “My blood pressure won’t stay down since they gave me a different pill.”

These aren’t complaints to brush off. They’re signals. And pharmacists are the only healthcare providers who see the full picture: the medication history, the manufacturer, the timing of the switch, the lab results.

If a patient reports a change after a generic switch, document it. Track the manufacturer. Check the Orange Book. Consider a therapeutic drug level test if applicable. Don’t wait for the prescriber to ask. Be the one who connects the dots.

What to Do When You Spot a Problem

Here’s a simple action plan any pharmacist can follow:

- Confirm the switch. Did the patient recently change from one generic to another? Or from brand to generic?

- Check the Orange Book. Is the generic AB-rated? Or BX?

- Identify the manufacturer. Write it down. Don’t rely on memory. Use your pharmacy system’s manufacturer field.

- Assess the drug class. Is it an NTI drug? An extended-release formulation? A complex delivery system like an inhaler or topical gel?

- Ask the patient. “Have you noticed any changes in how you feel since this medication changed?”

- Document everything. Use your pharmacy’s note system. Include the date, the manufacturer, the patient’s symptoms, and your actions.

- Report it. Submit a report to the FDA’s MedWatch program. It takes less than five minutes. And if enough pharmacists report the same issue, the FDA will investigate.

Don’t wait for a patient to be hospitalized. Flag it early. Your documentation might be the key that prevents the next serious event.

It’s Not About Trusting or Distrusting Generics

Generics are essential. They make life-saving drugs affordable. The vast majority are safe. But safety isn’t about blanket trust. It’s about vigilance.

Pharmacists don’t need to be drug manufacturers. But they do need to be detectives. When a patient’s condition changes after a switch, when a pill looks different, when a drug that always worked suddenly doesn’t-it’s not coincidence. It’s data.

The system works because pharmacists pay attention. Not because it’s perfect. But because we’re the last line of defense.

So the next time a patient says, “This one doesn’t feel right,” don’t say, “It’s the same drug.” Say, “Let’s figure out why.”

Are all generic drugs safe to use?

Most generic drugs are safe and effective, with the FDA requiring them to match brand-name drugs in active ingredients, dosage, and bioequivalence. However, some generics-especially those with BX ratings in the FDA’s Orange Book or complex formulations like extended-release versions-may have inconsistent performance. Pharmacists should flag these when patients report unexpected side effects or therapeutic failure.

Which generic drugs are most likely to cause problems?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) are most vulnerable, including levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, and tacrolimus. Extended-release formulations, such as diltiazem CD and metoprolol ER, also carry higher risk due to inconsistent drug release. Look-alike/sound-alike names like oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen increase the chance of dispensing errors.

How do I know if a generic is therapeutically equivalent?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book. Drugs rated "AB" are considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. Those rated "BX" are not. Always verify the rating before substituting, especially for NTI drugs. Many pharmacy systems display this code automatically, but pharmacists should confirm it manually when in doubt.

What should I do if a patient says a generic isn’t working?

Don’t dismiss it. Document the patient’s symptoms, the date of the switch, the manufacturer, and the drug formulation. Check the Orange Book for the drug’s therapeutic equivalence rating. Consider therapeutic drug monitoring if applicable. Contact the prescriber to discuss alternatives. Report the incident to the FDA’s MedWatch program to help identify potential systemic issues.

Can switching between generic manufacturers cause side effects?

Yes. Even if two generics are both AB-rated, differences in inactive ingredients, coating, or manufacturing processes can affect absorption and tolerability. Patients may report new nausea, dizziness, or changes in blood levels after switching manufacturers. This is especially common with NTI drugs and extended-release products. Tracking the manufacturer each time helps identify patterns.

Are pharmacists required to report problematic generics?

While not legally required in all states, pharmacists have a professional and ethical duty to report suspected issues. The FDA’s MedWatch program encourages reports from healthcare providers. Over 1,800 patient complaints about generics were submitted to the FDA between 2020 and 2023, many originating from pharmacist observations. Reporting helps trigger investigations and potential recalls.

Staying alert isn’t about distrust. It’s about responsibility. Every pill a pharmacist dispenses carries a promise: that it will do what it’s supposed to. When that promise breaks, it’s up to us to fix it.

Comments

Katy Bell

My grandma switched generics for her thyroid med last year and went from feeling fine to exhausted and depressed in two weeks. The pharmacist didn't catch it until she showed up at the counter crying. Turned out the new batch had a different filler that messed with absorption. She's back on the original generic now. Pharmacists are the real heroes here.

Javier Rain

As a pharmacist in rural Ohio, I see this every single day. Patients don’t know the difference between manufacturers, but they know when they feel off. I’ve had to call doctors so many times to reverse substitutions on warfarin and levothyroxine. The system is broken if we’re relying on patients to notice the difference before something goes wrong.

Ragini Sharma

lol so wait u r saying some generics r just bad? like fr? i thought all generics r the same? my cousin took some generic adderall and said it was like drinking hot sand???

Suresh Ramaiyan

It’s not about distrust-it’s about humility. We assume chemistry is exact, but biology is messy. A pill isn’t just its active ingredient; it’s the story of its manufacturing, its binders, its release profile. When we reduce a human being’s health to a cost-per-dose metric, we forget that the body doesn’t care about corporate margins. It only cares if the medicine works.

Pharmacists aren’t just dispensers-they’re translators between science and suffering. And too often, the system silences them.

The Orange Book isn’t a recommendation. It’s a lifeline. And if we ignore it, we’re not saving money-we’re gambling with lives.

There’s no shame in asking, ‘Is this the same?’ There’s shame in pretending it doesn’t matter.

Generics saved millions. But they didn’t save them by accident. They saved them because someone cared enough to check.

Let’s not turn vigilance into villainy.

Every time a patient says, ‘This doesn’t feel right,’ we owe them more than a shrug. We owe them a search. A call. A record. A stand.

Because in the end, medicine isn’t about pills. It’s about trust. And trust is built one careful decision at a time.

Laurie Sala

OH MY GOD I’M SO GLAD SOMEONE FINALLY SAID THIS!! I’VE BEEN TELLING MY PHARMACIST FOR MONTHS THAT THE NEW GENERIC FOR MY SEIZURE MED WAS MAKING ME DIZZY AND I’D GET THESE TERRIBLE HEADACHES AND SHE JUST SAID ‘IT’S THE SAME CHEMICAL’ LIKE THAT’S ENOUGH?? I ALMOST HAD A SEIZURE LAST MONTH BECAUSE OF IT!!

AND NOW I’M SCARED TO TAKE ANYTHING GENERIC BECAUSE WHO KNOWS WHAT’S IN THERE??

THE FDA IS ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL!!

WHY DON’T THEY RECALL THESE THINGS FASTER??

MY DOCTOR WON’T LISTEN EITHER!!

THIS IS A SCANDAL!!

Demi-Louise Brown

Professional responsibility isn’t optional. When a patient reports a change in response after a generic switch, it’s not anecdotal-it’s clinical data. Documenting manufacturer, timing, and symptoms isn’t bureaucracy-it’s prevention.

Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to detect these patterns. Ignoring them isn’t efficiency. It’s negligence.

Check the Orange Book. Confirm the imprint. Ask the question. That’s the job.

Matthew Mahar

my bad i just read this and i thought all generics were equal... i just assumed the fda checked everything... turns out they dont even check the coating?? wow. i feel dumb. also i think i took a bad batch of generic diltiazem last year and got chest pain... maybe that was why??

Henrik Stacke

As a UK-based pharmacist, I must say: this resonates deeply. Our NHS has similar pressures, and while we rarely see the same level of manufacturer-switching chaos, the principle remains. The ‘AB’ and ‘BX’ codes are just as vital here. I once had a patient on generic phenytoin whose levels dropped 40% after a supplier change. No one noticed until she had a seizure. We now flag all NTI drugs with a red sticker. Simple. Effective.

It’s not about opposing generics-it’s about respecting the science behind them.

shreyas yashas

in india we have this problem too but worse. some generics are made in factories with no quality control. i once saw a patient on warfarin who got a batch with half the dose. he had a stroke. the pharmacy didn’t even know the manufacturer changed. no one checks the orange book here. we just trust the box.

pharmacists here are overworked and underpaid. no one teaches them to look beyond the label.

but still - we try. we ask. we write notes. we call doctors.

it’s not enough. but it’s something.

Katy Bell

That’s why I always write the manufacturer on the prescription sticker now. Even if the system auto-fills it. If a patient comes back saying they feel weird, I can trace it in seconds. No guesswork. Just facts.

Brandy Walley

Ugh so now we’re supposed to be pharmacists AND detectives AND data entry clerks? The real problem is that insurance companies force switches to the cheapest generic no matter what. If you don’t fill it, you lose your job. Meanwhile, the CEO of the drug company is on a yacht in the Med. This isn’t about vigilance. It’s about capitalism eating healthcare alive.