When you pick up a prescription, you might not think about whether it’s a brand-name drug or a generic. But behind the counter, state governments are quietly pushing pharmacists-and patients-to choose the cheaper option. It’s not magic. It’s policy. And it’s saving billions.

Why States Care About Generic Drugs

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper-they’re the same. Same active ingredients. Same effectiveness. Same safety. The only difference? Price. A generic version of a popular blood pressure pill can cost $4 instead of $150. That’s not a typo. And when you multiply that across millions of prescriptions, the savings add up fast. States aren’t doing this out of charity. Medicaid alone spends over $100 billion a year on prescriptions. With rising drug costs and strained budgets, every dollar saved on generics means more money for nursing care, mental health services, or rural clinics. That’s why 46 out of 50 states have set up Preferred Drug Lists-curated lists of medications that are covered with lower copays or no prior authorization.How Preferred Drug Lists Work

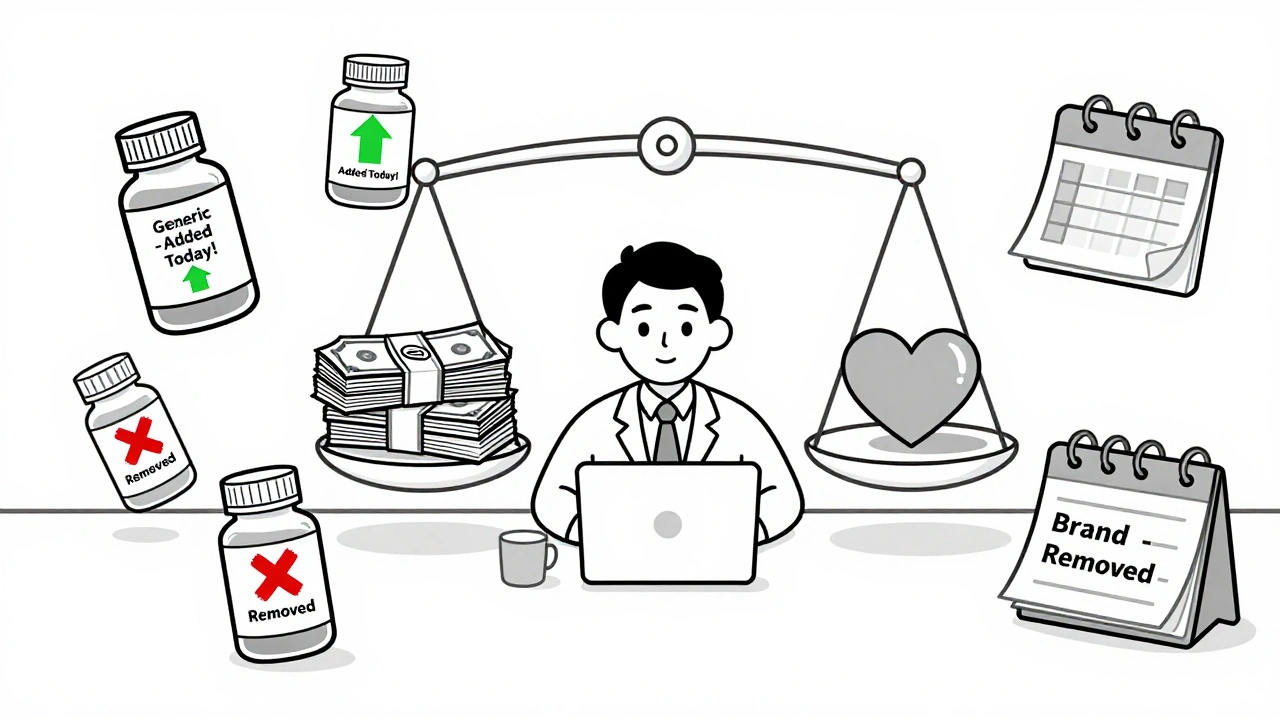

Think of a Preferred Drug List (PDL) like a grocery store’s “store brand” section. It’s not that the name-brand items are banned. But if you pick the more expensive one, you pay more out of pocket. In states with PDLs, if your doctor prescribes a brand-name drug that’s not on the list, you or your insurer have to jump through hoops. Maybe you need prior authorization. Maybe you pay a higher copay. Sometimes, the pharmacist can’t even fill it unless the doctor explains why the generic won’t work. These lists aren’t static. Twenty states review them every year. Ten do it quarterly. That means if a new generic hits the market and proves it’s safe and effective, it can get added fast. And if a brand-name drug raises its price? It might get kicked off the list. The kicker? Forty-six states negotiated extra rebates with drugmakers on top of the federal minimum. That’s not just policy-it’s negotiation. States are playing hardball to get better prices.The Real Game Changer: Presumed Consent Laws

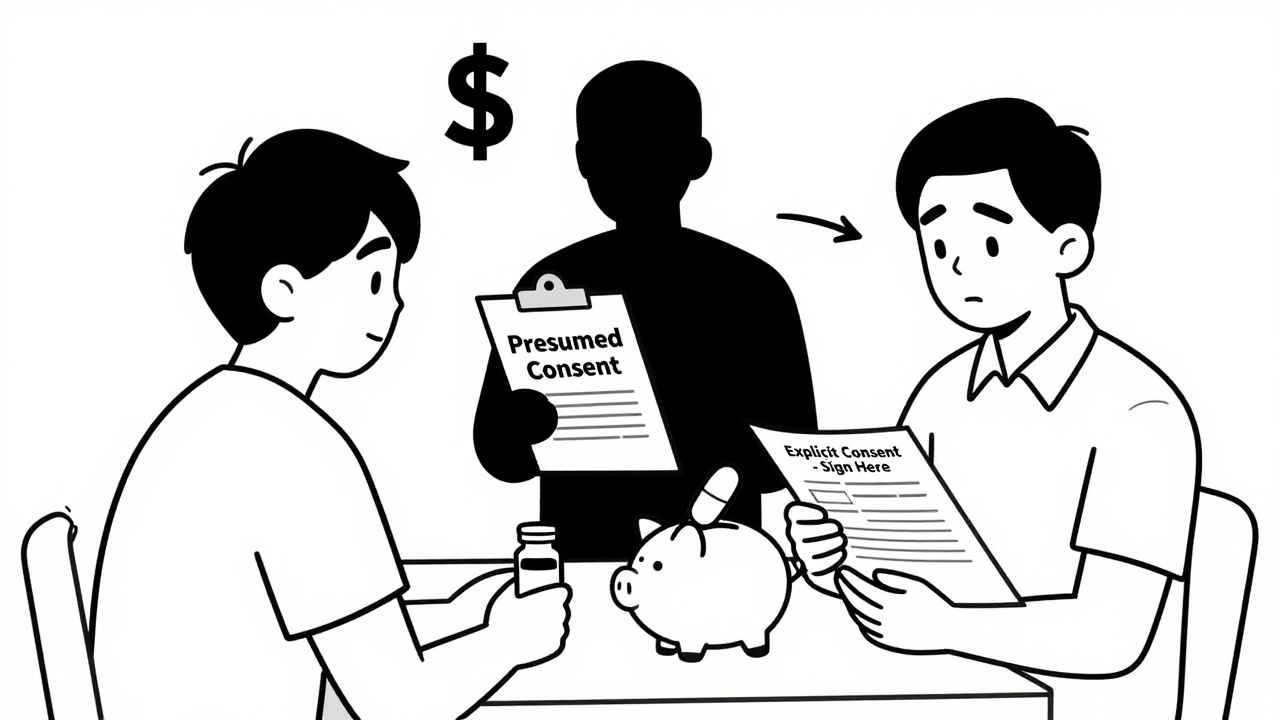

Here’s where things get interesting. Some states let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a generic without asking you first. That’s called presumed consent. Other states require you to say yes before the switch happens. That’s explicit consent. A 2018 NIH study found a clear winner: presumed consent increases generic dispensing by 3.2 percentage points. That might sound small, but it’s the same effect as raising the price of brand-name drugs by $3. And if all 39 explicit consent states switched to presumed consent? They’d save an estimated $51 billion a year. Why does this work? Because most people don’t care. They just want the pill to work. And if the pharmacist hands them a cheaper version without a fuss, they take it. But if they have to sign a form or ask a question? They often stick with the brand-especially if they’re not sure the generic will work the same.Copay Differentials: Putting the Pressure on Patients

States aren’t just nudging pharmacists. They’re nudging you. Many states structure copayments so that generics cost $5, while brand-name drugs cost $30 or more. That’s not a mistake. It’s intentional. And it works. People who are cost-conscious-especially those on fixed incomes or with chronic conditions-switch to generics because they have to. In the late 90s, the gap between pharmacy dispensing fees for brand and generic drugs was barely $0.08. That means pharmacists made almost the same profit either way. So why would they push generics? Because patients did. When the copay difference grew, so did generic use. Today, 15 states and Puerto Rico have laws that require or encourage these copay differentials. But even in states without laws, many Medicaid programs and private insurers do it anyway. It’s become standard practice.

What Doesn’t Work: Mandatory Substitution Laws

You might think forcing pharmacists to substitute generics would be the most effective tactic. But research shows it’s not. Mandatory substitution laws-where pharmacists must switch unless the doctor says no-have almost no measurable impact. Why? Because pharmacists already have a financial incentive to do it. They get paid the same whether they dispense a $4 generic or a $150 brand. And they know patients prefer the cheaper option. So mandating it doesn’t change behavior. It just adds paperwork. The real leverage isn’t in forcing pharmacists. It’s in making patients feel the cost difference.The Hidden Problem: When Generics Disappear

There’s a dark side to all this cost-cutting. Generic manufacturers are caught in a trap. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program requires them to pay back a percentage of their sales to states. But here’s the catch: if the price of ingredients goes up, or if there’s a shortage, or if the market gets crowded with competitors, the rebate formula doesn’t adjust. So the drug stays the same price-but the rebate keeps growing. Avalere Health found five scenarios where generic manufacturers end up losing money on Medicaid sales. And when that happens? They stop making the drug. Or they pull it from the market entirely. That’s right. The very policies meant to increase generic access can cause shortages. One state might save $10 million by pushing generics. But if the only generic for a critical drug vanishes? That’s a public health crisis.340B and the Safety Net

Hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients get special pricing through the 340B Drug Pricing Program. They can buy drugs-brand and generic-at 20% to 50% off. That’s huge. But here’s the twist: states have to reimburse these clinics based on what they actually paid, not what the drug normally costs. After a 2016 CMS rule, states had to cap reimbursement at the 340B ceiling price. That meant some clinics got paid less than they spent. It created chaos. Some clinics stopped stocking certain generics because they couldn’t afford to buy them at 340B prices and then get reimbursed even less. So even with all the incentives, access didn’t always improve.

Comments

Steve Sullivan

I just got my lisinopril for $2 at Walmart last week. No paperwork, no drama. Just walked in, got my pill, paid two bucks. This is what they should do everywhere. 🙌

Kathy Haverly

Oh please. This whole 'generic = safe' myth is just Big Pharma's way of controlling you. You think they don't cut corners on inactive ingredients? I've had generics that made me feel like I was being slowly poisoned. And now they're pushing this 'presumed consent' nonsense? That's not healthcare-it's coercion.

Andrea Petrov

You know who benefits from this? The same people who run the FDA and the CDC. They're all on the same payroll. The 'same active ingredients' line? Total lie. The fillers are different, and those are what cause the side effects. I read a study-well, someone on a forum cited a study-that showed generics have 17% more contaminants. They don't tell you that. They want you to be docile and take the cheap stuff.

Suzanne Johnston

I'm from the UK, and we've had this system for decades. The NHS doesn't care if it's brand or generic-it cares if it works. And guess what? It works. People live longer, hospitals run smoother, and no one goes bankrupt because of a prescription. This isn't some radical idea. It's common sense. Why do we make it so complicated in the US?

George Taylor

This article is a joke. 'Presumed consent'? That's just another word for 'they're lying to you.' And 'copay differentials'? That's financial coercion. People with chronic illness can't afford to 'choose'-they're forced. And don't even get me started on the 340B mess. This whole system is a house of cards built on greed and bad math.

ian septian

Generics save lives. Period.

Chris Marel

I come from Nigeria, where we don’t even have access to generics most of the time. People here pay 10x more for the same pills because of import taxes and corruption. I’m glad someone’s fighting for this. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than nothing. We need more of this, not less.

Evelyn Pastrana

So let me get this straight-you're telling me that if I'm poor, I get a $4 pill, and if I'm rich, I get a $150 pill that does the exact same thing? And you call this a system? 😂 I mean, at least be honest about it. Call it 'Medicaid Medication Roulette' and be done with it.

Carina M

The moral implications of this policy are deeply concerning. To presume consent on a medical intervention-no matter how trivial it may seem-is a violation of bodily autonomy. The state has no right to substitute pharmaceuticals without explicit, informed, and documented patient consent. This is not efficiency; it is paternalism dressed in the clothing of fiscal responsibility.

William Umstattd

This is a national disgrace. You're telling me that millions of Americans are being forced into cheaper drugs by bureaucrats who have never even held a prescription? And you call this 'empowerment'? No. This is the slow, quiet death of patient dignity. They don't care if you feel weird after taking the generic. They just care that their budget didn't go over by 0.3%. We are not numbers. We are not line items.

Elliot Barrett

The whole 'presumed consent' thing is just a PR stunt. Pharmacists don't care. They just want to get through their shift. And patients? They don't know the difference. So they take it. And then they blame the doctor when it doesn't work. This isn't policy-it's negligence.

Tejas Bubane

I work in pharma logistics in India. These 'generic savings' are a myth. The real savings go to middlemen, not patients. And the quality? Half the generics I see are fake or expired. You think your $4 pill is safe? Maybe. Maybe not. The system is rigged to look good on paper while the real people suffer.

Ajit Kumar Singh

I dont care what they say about generics they work fine i been taking them for 10 years for my bp and my sugar and i aint dead yet so stop the drama

Angela R. Cartes

I used to be a nurse. I've seen people skip doses because they can't afford the brand. Then they end up in the ER. So yeah, I'm all for the $2 pills. But I'm also terrified that the next one to disappear will be the only one that works for someone with epilepsy. We're playing Russian roulette with people's lives and calling it 'fiscal responsibility'. 💔

Michael Robinson

We talk about choice, but the real choice isn't between brand and generic. It's between taking the pill or not taking it at all. If you're making $15 an hour and your copay is $30, you're not choosing-you're surviving. The system doesn't care if you're angry. It just wants you to live long enough to pay your taxes. That's the real philosophy here: survival over dignity.