When a patient gets a biosimilar instead of the original biologic drug, they’re not getting a copy like a generic pill. Biosimilars are made from living cells-complex, delicate, and sensitive to tiny changes in how they’re made. That’s why their safety doesn’t just rely on the same checks as a generic drug. It needs something more: adverse event monitoring that’s built to catch differences you can’t see in a lab.

Why Biosimilars Need Special Safety Tracking

Generics are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts. A 10mg tablet of generic lisinopril is the same molecule as the brand version. Biosimilars? Not even close. They’re large, complex proteins-sometimes over 10,000 times bigger than a small-molecule drug. Even small changes in the manufacturing process-like a different cell line, temperature, or purification step-can alter how the body reacts to them. That’s why immunogenicity is the big concern: the body might recognize the biosimilar as foreign and launch an immune response, leading to reduced effectiveness or dangerous side effects like anaphylaxis or neutralizing antibodies.The FDA approved its first biosimilar, Zarxio, in 2015. Since then, over 35 have been approved in the U.S. alone. In Europe, there are 43. But with each new biosimilar entering the market, the challenge grows: how do you know if a bad reaction came from the reference product or the biosimilar? If a patient gets a rash after switching, is it the drug-or something else? Without clear tracking, you can’t tell. And if you can’t tell, you can’t fix it.

How Adverse Events Are Reported

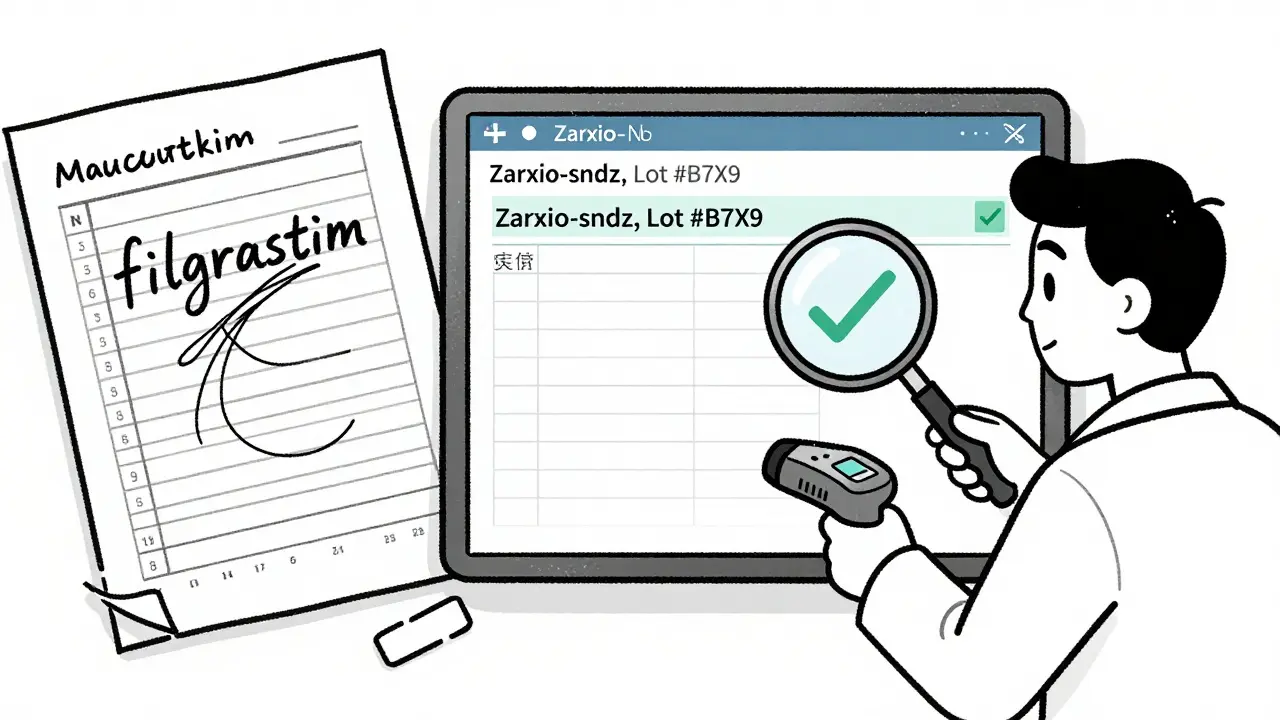

The backbone of biosimilar safety monitoring is spontaneous reporting systems. These are databases where doctors, pharmacists, and patients report side effects. In the U.S., that’s FAERS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System). In Europe, it’s EudraVigilance. In Canada, it’s the Canada Vigilance Program. These systems collect over 15 million reports globally every year.But here’s the problem: most reports don’t include the manufacturer’s name. A doctor might write “filgrastim” without saying whether it was Neupogen (the reference) or Zarxio (the biosimilar). A 2022 U.S. survey found that 63.4% of physicians were confused about how to document biosimilar use. In one study, only 37.8% of pharmacists knew the exact details required to report a biosimilar adverse event correctly.

That’s why product identification matters. The FDA started requiring a unique four-letter suffix for biosimilars in 2017-like “-sndz” for Zarxio. Canada doesn’t use suffixes. Instead, they require the brand name to be recorded in every report. In Spain, since 2020, electronic health records have been required to show the exact manufacturer. The result? Adverse event reporting accuracy jumped from 58% to 92%.

The Two Systems: Passive and Active Surveillance

There are two ways to monitor safety: passive and active.Passive surveillance is what most people think of: waiting for reports to come in. It’s cheap, easy to scale, and used everywhere. But it’s slow. And it’s incomplete. A 2021 IQVIA analysis found that biosimilar-specific reports made up only 0.3% of all biologic reports-even though biosimilars accounted for 8.7% of prescriptions. That gap suggests many events are being missed or misattributed.

Active surveillance is different. It’s proactive. Systems like the FDA’s Sentinel Initiative dig into real-world data: insurance claims, hospital records, pharmacy logs. They look for patterns-like a spike in hospitalizations for a specific biosimilar in a certain region. This method can catch signals that spontaneous reports miss. For example, if patients on a particular biosimilar start having more cases of neutralizing antibodies, active surveillance can flag it within weeks, not months.

Canada, the EU, and the U.S. all use both systems. But only the U.S. and Canada require biosimilar manufacturers to submit detailed Risk Management Plans (RMPs) that include specific immunogenicity monitoring. The EMA says biosimilars follow the same rules as the original biologic-no extra requirements. That’s a big difference in philosophy.

What’s in the Risk Management Plan?

Every biosimilar application must include a Risk Management Plan. This isn’t just a formality. It’s a living document that outlines exactly how the company will track safety after the drug hits the market. For biosimilars, the plan must include:- How immunogenicity will be monitored in real-world use

- How to distinguish adverse events between the biosimilar and the reference product

- How batch/lot numbers will be recorded and reported

- Plans for post-marketing studies, especially if the drug is designated as “interchangeable”

Health Canada’s 2022 guidelines are the strictest: they require a clear method to separate biosimilar reports from reference product reports. The FDA requires the same for interchangeable biosimilars, which were approved for the first time in 2023. These products can be swapped at the pharmacy without the prescriber’s permission-so tracking becomes even more critical.

But here’s the catch: most hospitals still can’t track biosimilars properly. A 2022 HIMSS survey found only 42.6% of U.S. hospitals had systems that captured the manufacturer name in electronic records. That means if a patient has a reaction, the pharmacy might not even know which product they got.

Global Differences in Tracking

The way biosimilars are monitored varies wildly by country:- United States: Uses suffixes, requires PSURs every 6 months for the first 2 years, mandates bi-weekly database screening, and has a 21st Century Cures Act requirement for quarterly public reports.

- European Union: No special biosimilar rules-same as the reference product. Uses EudraVigilance with standardized MedDRA coding. No mandatory suffixes or batch tracking.

- Canada: No suffixes. Requires brand name and manufacturer in every report. Mandates batch-level traceability since January 2023. Non-compliance can cost up to $500,000 CAD.

- India: Requires PSURs every 6 months for two years.

These differences create real problems. A patient might get a biosimilar in the U.S., then move to Canada. Their adverse event report might not follow them. A signal detected in Europe might not be visible in the U.S. database because of different coding. That’s why the WHO and ICH are pushing for global standards-especially for batch tracking and terminology.

Real-World Evidence and AI Are Changing the Game

The future of biosimilar safety isn’t just in forms and reports. It’s in data. And AI.Companies like ArisGlobal and Oracle Health Sciences now offer cloud-based pharmacovigilance platforms that use machine learning to scan clinical notes, lab results, and discharge summaries for signs of immunogenicity. Natural language processing tools can pull out phrases like “patient developed anti-drug antibodies after switch” from unstructured doctor’s notes-something humans would miss.

EMA launched VigiLyze in 2022, an AI system that analyzes 1.2 million new case reports a year with 92.4% accuracy in detecting safety signals. That’s faster, cheaper, and more precise than manual review.

But these tools cost money. Mid-sized companies spend $250,000 to $500,000 to implement them. And not every country can afford it. That’s creating a gap between rich and poor healthcare systems.

What Patients and Doctors Need to Know

Patients aren’t always told what they’re getting. A 2022 Arthritis Foundation survey found that 41.2% of patients on biosimilars didn’t know which product they received. That’s dangerous. If you have a bad reaction, you can’t report it properly. You can’t tell your doctor. You can’t even ask for a different one.Doctors need training. Pharmacists need clear labeling. Pharmacies need systems that auto-fill the manufacturer name when a biosimilar is dispensed. And every prescription should include the brand name and manufacturer-no shortcuts.

Here’s what you can do:

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the reference product or a biosimilar? What’s the brand name?”

- Write down the name of the product you receive every time.

- Report any new side effects-even if you’re not sure what caused them.

- Keep a symptom diary: date, dose, reaction, product name.

These steps aren’t just helpful-they’re essential. Without accurate reporting, we can’t detect a problem until it’s too late.

The Big Picture: Why This Matters

Biosimilars are saving billions in healthcare costs. In the U.S., they’ve cut prices for drugs like Humira by up to 60%. But if safety isn’t monitored properly, trust collapses. Patients stop using them. Doctors refuse to prescribe them. The whole system fails.Right now, we’re in a transition. The tools exist. The data is there. The regulations are evolving. But implementation is lagging. The real challenge isn’t science-it’s systems. It’s training. It’s communication.

By 2028, the global biosimilars market will hit $34.9 billion. By 2030, there could be over 300 biosimilars on the market. We need a safety system that can handle that scale. Right now, it’s not ready.

But it can be. With better traceability. With AI. With mandatory batch reporting. With doctors and patients who know what they’re taking-and aren’t afraid to speak up.

What’s Next for Biosimilar Safety?

The International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme is working on a global unique identifier system for biologics-like a barcode for every batch. Pilot studies in Switzerland show it could reduce misattribution errors by 73.5%. The cost? $1.8 billion globally. But the savings in avoided adverse events? Likely over $10 billion a year.Regulators are moving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on interchangeable biosimilars now requires post-marketing studies to test switching effects. Canada’s new batch-level tracking rules are the strictest in the world. The EU is starting to rethink its “no extra rules” stance.

The question isn’t whether we can monitor biosimilars safely. It’s whether we’re willing to do it right.

Comments

Robert Way

so i got my humira biosimilar last week and my arm got all red and itchy like wtf is this i thought it was the same as the original but now im scared to take the next shot lol

Allison Deming

It is both alarming and profoundly irresponsible that the regulatory frameworks governing biosimilar safety remain so fragmented across jurisdictions. The absence of standardized, mandatory batch-level traceability-particularly in the European Union-undermines the very foundation of pharmacovigilance. When adverse events are conflated due to inadequate product identification, the integrity of post-marketing surveillance collapses. This is not merely a logistical oversight; it is a systemic failure that endangers patient safety in the name of cost-cutting. The FDA’s suffix requirement, while imperfect, at least attempts to mitigate this chaos. Why other regions refuse to adopt similar measures remains a mystery wrapped in bureaucratic inertia.

Susie Deer

USA does it right europe is just lazy and india cant even spell pharmacovigilance

TooAfraid ToSay

you think this is about safety but its really about corporate control. who owns the data when you track every batch? who profits when they blame the biosimilar instead of the system? i saw a guy on YouTube say the FDA is in bed with big pharma and theyre making us pay extra to be guinea pigs. i dont trust any of this

Dylan Livingston

Oh how quaint. We’ve moved from ‘trust the science’ to ‘trust the suffix’ as if a four-letter code magically transforms a $10,000 vial into something less terrifying. The real tragedy isn’t poor reporting-it’s that we’ve outsourced our health to a system where the only thing more opaque than the manufacturing process is the paperwork meant to track it. And yet, somehow, we still act surprised when people die from an antibody response no one bothered to label properly. How very 2020s of us.

Andrew Freeman

why do we even need suffixes i mean its still the same drug right like come on its not like its a different brand of toilet paper

says haze

The entire biosimilar paradigm is a neoliberal illusion wrapped in regulatory lipstick. We pretend that complexity can be reduced to a formula, that living systems can be replicated with statistical confidence, and that patient outcomes can be quantified without acknowledging the ontological gap between molecule and meaning. The real issue isn’t traceability-it’s epistemological. We are trying to control the uncontrollable. The AI systems you celebrate? They’re just glorified pattern-matchers trained on data that’s already corrupted by misattribution. You’re not solving the problem. You’re automating the delusion.

Alvin Bregman

im just glad we have any biosimilars at all honestly. i know tracking is messy but its better than nothing. i had a friend on a biosimilar and she said it worked just as good as the brand and saved her like 2k a year. maybe we just need better training for docs and pharmacists instead of overcomplicating it with tech

Sarah -Jane Vincent

you think this is about safety but its actually a plot by the WHO to implant microchips in biologics. i checked the EMA website and their logo has a hidden 666 symbol. and why do they only track batches in canada? because that’s where they test the tracking tech on real people. my cousin works at a pharmacy and she said they started labeling everything with QR codes in 2023. that’s not traceability-that’s surveillance.

Henry Sy

man i just got switched to a biosimilar last month and my body felt like it was being slowly replaced by a robot. like i could feel the antibodies forming. i told my doc and he just shrugged. now im convinced the drug company is using my immune system to train their AI. they’re harvesting my rage. i swear i can hear the servers humming at night.

Anna Hunger

Thank you for this comprehensive and meticulously researched overview. The disparities in global pharmacovigilance frameworks are indeed concerning, and the call for standardized batch-level traceability is both timely and necessary. I would respectfully suggest that healthcare institutions prioritize interoperable electronic health record integration as a foundational step-ensuring that manufacturer, lot number, and product designation are captured at the point of dispensing. Without this, all other initiatives, however technologically sophisticated, remain fundamentally compromised. Patient safety must be engineered into the system-not bolted on after the fact.